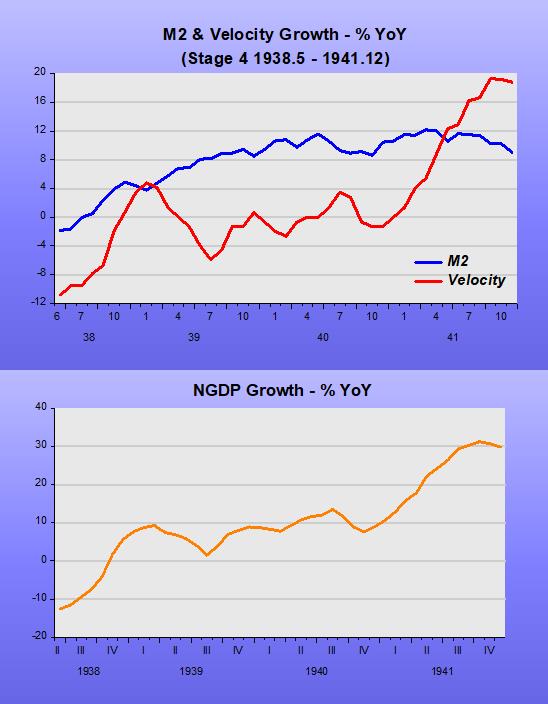

Many like to compare the Covid19 contraction with the Great Depression. In addition to the nature of the two contractions being completely unrelated, while in the first two months of the Covid19 crisis (from the February peak to the April trough) RGDP dropped 15%, it took one year from the start of the Great Depression for RGDP to drop by that amount.

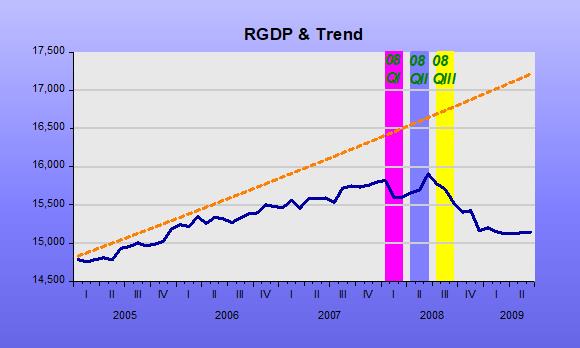

Although the Covid19 shock has also no common element with the Great Recession, a comparison between the two is instructive from the monetary policy point of view. This is so because the Great Recession was the “desired outcome” of the Fed´s monetary policy. Bear with me and I´ll try to convince you that is not a preposterous statement.

Motivated by the belief that the 2008-09 recession originated with the losses imposed on banks by their exposure to real estate loans and propagated through a consequent breakdown in the ability of banks to get loans to credit-worthy borrowers, government, the Fed and regulators intervened massively in credit markets to spur lending.

Bernanke´s January 13, 2009 speech “The crisis and the policy response” summarizes that view:

“To stimulate aggregate demand in the current environment, the Federal Reserve must focus its policies on reducing those spreads and improving the functioning of private credit markets more generally.”

Bernanke´s “credit view” of the monetary transmission process is well established. Two articles support that view.

His flagship 1983 article is titled “Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.”

“…we focus on non-monetary (primarily credit-related) aspects of the financial sector–output link and consider the problems of debtors as well as those of the banking system. We argue that the financial disruptions of 1930-33 reduced the efficiency of the credit allocation process; and that the resulting higher cost and reduced availability of credit acted to depress aggregate demand.”

His 1988 primer “Monetary Policy Transmission: Through Money or Credit?”

“…The alternative approach emphasizes that in the process of creating money, banks extend credit (make loans) as well, and their willingness to do so has its own effects on aggregate spending.”

For details on the Fed´s credit market interventions (with the purpose of reducing spreads, which to the Fed is a sign of credit market dysfunction), see chapter 15 of Robert Hetzel´s “The Great Recession”

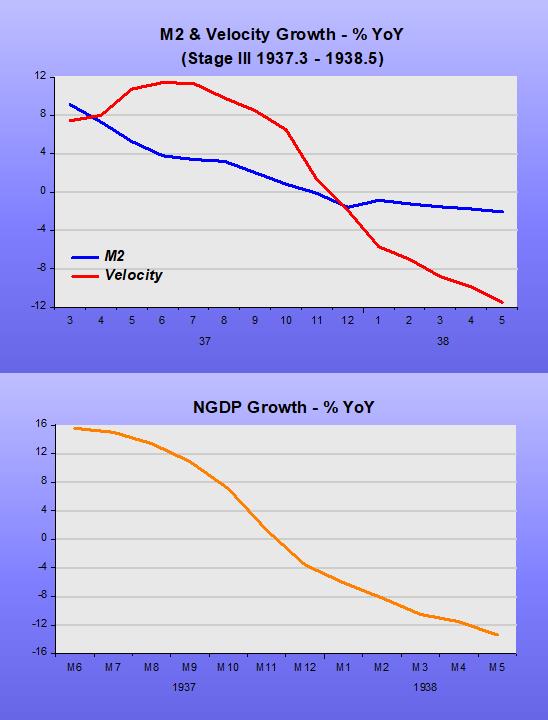

“The answer given here is that policy makers misdiagnosed the cause of the recession. The fact that lending declined despite massive government intervention into credit markets indicated that the decline in bank lending arose not as a cause but as a response to the recession, which produced both a decline in the demand for loans and an increase in the riskiness of lending.

In their effort to stimulate the economy, policy makers would have been better served by maintaining significant growth in money as an instrument for maintaining growth in the dollar expenditures [NGDP growth] of the public rather than on reviving financial intermediation”

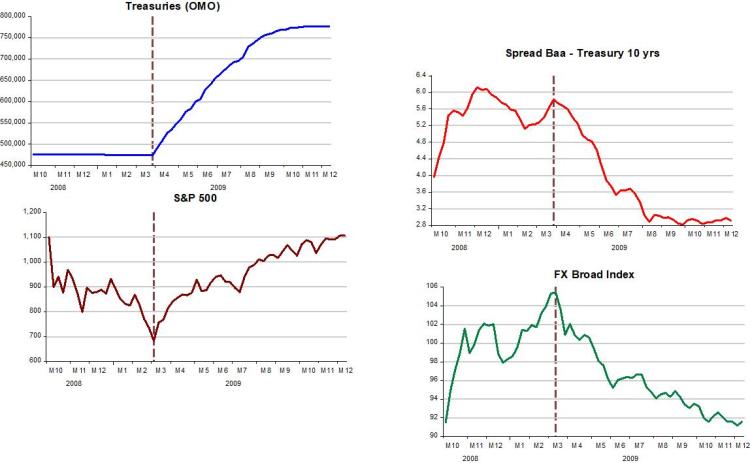

The charts below attest to that fact insofar as spreads began to fall, the dollar exchange rate began to depreciate and the stock market began to rise, only after the Fed implemented quantitative easing (QE1) in March 2009.

The purchase of treasuries by the Fed was what “saved the day”, not the array of credit policies that had been implemented for several months prior. Note, however, that the monetary policy sail was only at half-mast. On October 2008, the Fed had introduced IOER (interest on reserves), so that the rise in the monetary base from all the Fed´s credit policy would not “spillover” into an increase in the money supply. (The rise in the reserve/deposit (R/D) ratio in fact more than offset the rise in the base, so money supply growth was negative).

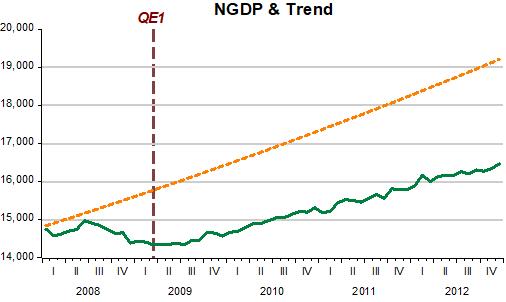

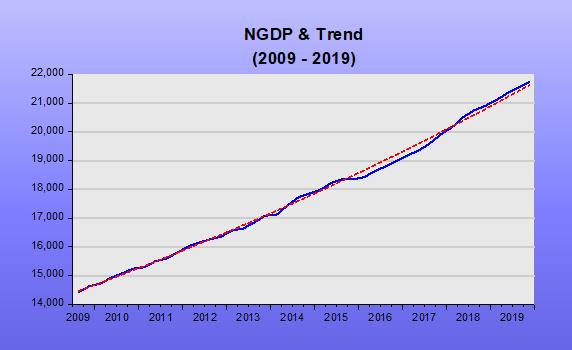

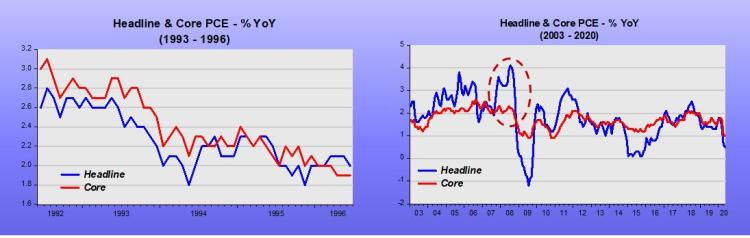

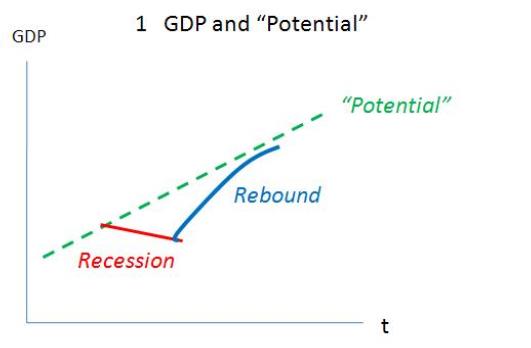

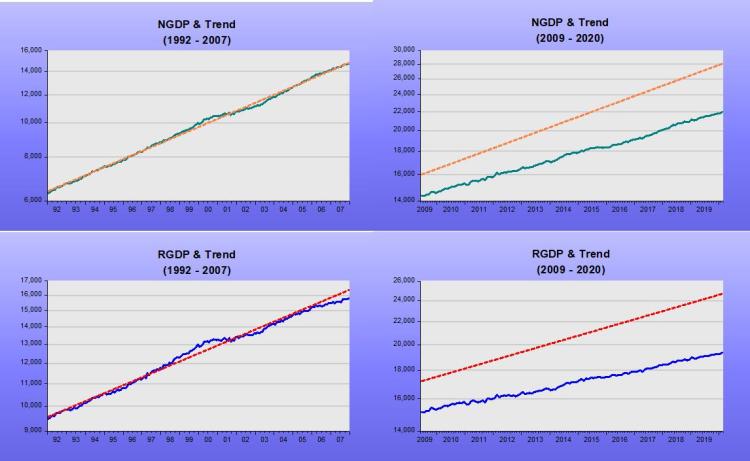

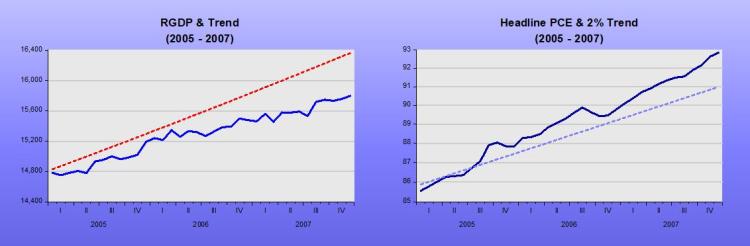

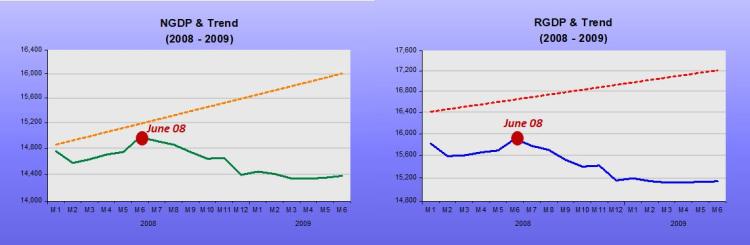

What QE did was to increase the velocity of circulation. With that, spending (NGDP) growth stopped falling and then began to rise slowly. As the next chart shows, the Fed (due to inflation worries) never allowed NGDP growth to make-up for the previous drop, “calibrating” monetary policy to keep NGDP growth on a lower trend path and lower growth rate.

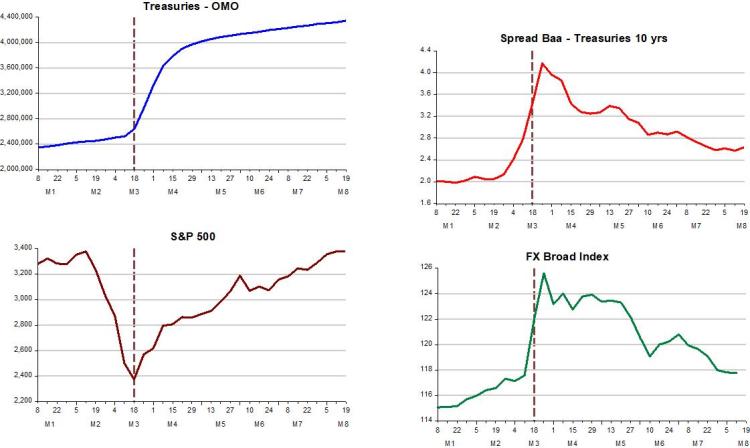

Skipping to 2020, when the Covid19 shock hit, NGDP tanked. With spreads rising, the Fed again, now under Jay Powell (who must have learned “creditism” from his time with Bernanke), quickly announced a large batch of programs to intervene in credit markets to sustain financial intermediation.

While in the U.S., it was all about “closing spreads”, in Europe the sentiment was the opposite:

Christine Lagarde (March 12): “We are not here to close spreads”

Laurence Meyer (March 17): “The Fed is here to close spreads”

In “Covid19 and the Fed´s Credit Policy”, Robert Hetzel writes:

“…When financial markets actually did continue to function, Chairman Powell claimed that it was because of the announcement effect that the programs would become operational in the future…”.

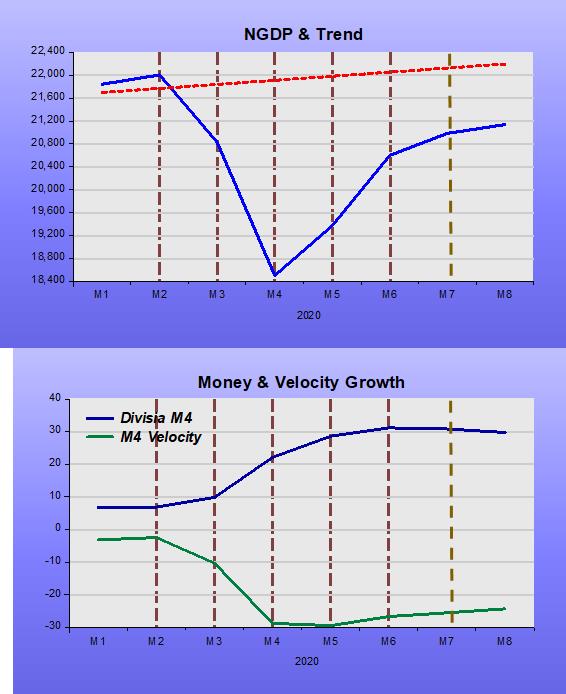

Looking at the charts for the period, we again observe that spreads fell (markets functioned) when monetary policy – through open market operations, with the Fed buying treasury securities – becomes expansionary. The difference, this time, is that the monetary policy sail was at “full mast”, so that money supply growth rose fast.

Compared to the post 2008-09 period, NGDP reversed direction in a V-shape fashion (data on monthly NGDP to June from Macroeconomic Advisers). This time around, it seems the Fed is set in making-up for the lost spending, returning NGDP to the trend level that prevailed from 2009 to 2019.

Going forward, once the economy fully reopens the Fed will have to make clear that monetary policy will the conducted to maintain nominal stability (i.e. NGDP cruising along the trend level path it was on previously). Given the degree of fiscal “overkill” that has been practiced, the Fed will have to resist pressures to maintain an overly expansionary monetary policy to relieve fiscal stress through inflationary finance.