As I will show, it has also been doing NGDP-LT, albeit with a “variable” Level Trend. It´s amazing that it took them one and a half years to come up with a framework that had been in place for so long!

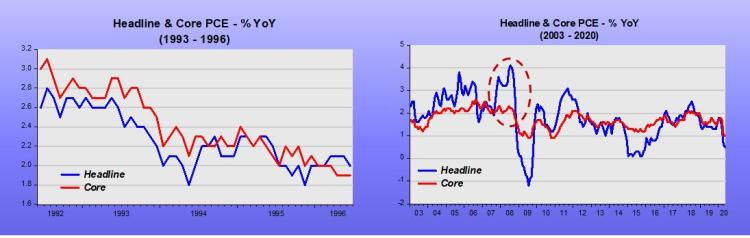

The chart below shows that the core PCE has closely followed the trend (estimated from 1992 to 2005). The trend reflects a 1.8% average inflation, not the 2% average target, but close.

To illustrate the fact that the Fed has effectively been practicing AIT, I zoom in on two periods (outside the estimation interval) to show an instance of adjustment from above and one from below.

Even now, after the Covid19 shock, it is trying to “make-up”!

The “other Policy framework” the Fed has been “practicing” with for over three decades is NGDP Level Targeting.

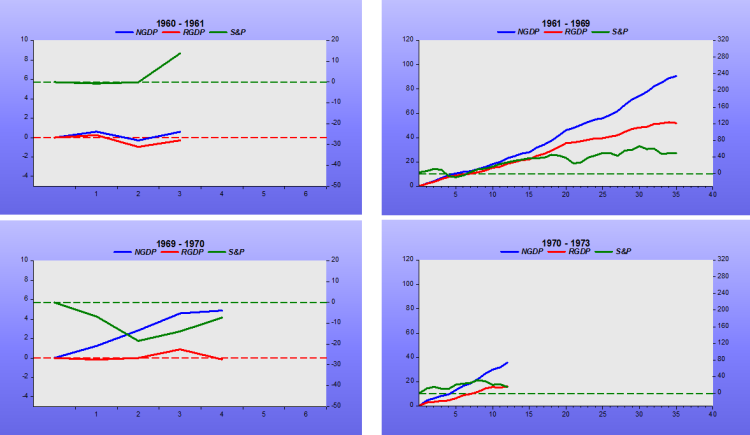

The set of charts below show how NGDP has evolved along the same trend during different periods.

The following chart zooms in on 1998 – 2004 and shows that the Fed first was excessively expansionary (reacting to the Asia & Russia +LTCM crises) and then “overcorrecting” in 2001-02 before trying to put NGDP back on the level trend, which it did by 2004. Many have pointed out that the Fed was too expansionary in 2002-04, blaming it for stoking the house bubble and the subsequent financial crisis. However, the only way the Fed can “make-up” for a shortfall in the level of NGDP is for it to allow NGDP to grow above the trend rate for some time!

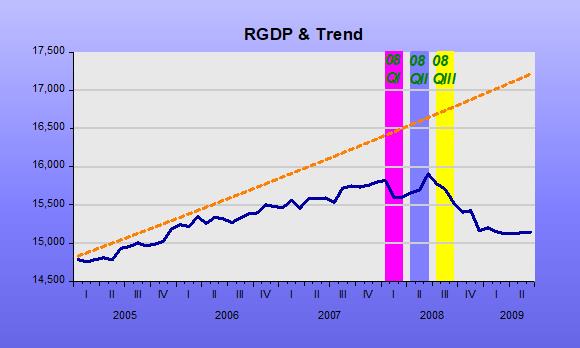

As the next to last chart shows, 2008 was a watershed on the Fed´s de facto NGDP-LT framework. As shown in the chart, in June 2008 the Fed “gave up” on the strategy, “deciding” it would be “healthier” for aggregate nominal spending (NGDP) to traverse to a lower level path and lower growth rate.

If you doubt that conjecture, read what Bernanke had to say when summarizing the June 2008 FOM Meeting.

Bernanke June 2008 FOMC Meeting:

“I’m also becoming concerned about the inflation side, and I think our rhetoric, our statement, and our body language at this point need to reflect that concern. We need to begin to prepare ourselves to respond through policy to the inflation risk; but we need to pick our moment, and we cannot be halfhearted.”

He certainly got what he wished for. As the next chart indicates from the end of the Great Recession to just prior to the Covid19 shock, NGDP was spot on the new lower trend path alongside a reduced growth rate.

The Covid19 shock tanked NGDP. This was certainly different from what happened in 2008. Then, it was a monetary policy “choice”. Now, it was virus related. The other thing is that at present, instead of being worried about inflation being too high or risking getting out of control, the fear is with inflation being too low.

That worry, which has been evident for some time, led that Fed to unveil a new monetary policy framework, AIT, for average inflation targeting. As I argued before, this framework has been in place for decades!

The last chart above indicates that monetary policy is “trying” to make-up for the drop in NGDP from the “Great Recession Trend” it was on. We also saw that the Core PCE Index is on route to get back to its decades-long trend.

Given that inflation is a monetary phenomenon, these two facts are related. For inflation to go up (as required to get the price level back to the trend path) NGDP growth has to rise. However, many FOMC members are squeamish. We´ve heard some manifest that they would “be comfortable with inflation on the 2.25% – 2.5% range”.

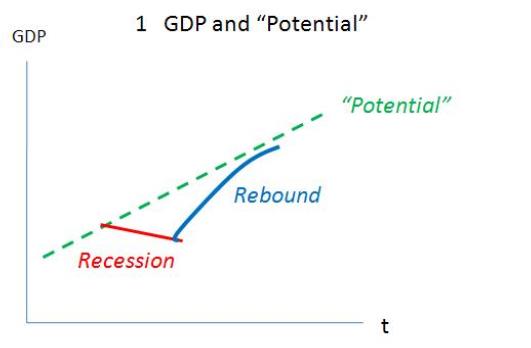

The danger, given the presence of “squeamish” members, is there could come a time when the Fed would reduce NGDP growth before it reached the target path. Inflation would continue to rise (at a slower, “comfortable”, rate) and reach the price path while, at the same time, the economy remains stuck in an even deeper “depressive state” (that is, deeper than the one it has been since the Fed decided in 2008).

That is exactly what happened following the Great Recession. NGDP growth remained stable (at a lower rate than before) and remained “attached” to the lower level path the Fed put it on.

These facts show two things:

- To focus on inflation can do great damage to the economy. For example, imprisoning it in a “depressed state”.

- Since the Fed has kept NGDP growth stable for more than 30 years, and freely choosing the Level along which the stable growth would take place, the implication is that it has all the “technology” needed to make NGDP-LT the explicit (or just de facto) monetary policy framework. As observed, that framework is perfectly consistent with IT, AIT or PLT!