Recently, manifestations about rising inflation following the Covid19 have increased substantially. Two recent examples illustrate, with both appealing to the QTM:

- The quantity theory of money today provides – as it always has done – a theoretical framework which relates trends in money growth to changes in inflation and nominal GDP over the medium and long term.

A condition for the return of inflation to current target levels is that the rate of money growth is reduced back towards annual rates of increase of about 6 per cent or less.

2. The quantity theory of money, the view that the money supply is the key determinant of inflation, is dead, or today’s mainstream tell us. The Federal Reserve is now engaged in a policy that will either put the nail in the quantity theory’s coffin or restore it to the textbooks. Sadly, if the theory is alive and wins out, the economy is in for a very rough ride.

All those that appeal to the QTM to argue, “Inflation is coming”, forget that in 1971 Milton Friedman published in the JPE “A monetary theory of nominal income”, in which he argued for using the quantity theory to derive a theory of nominal income rather than a theory of either prices or real income.

There he asks; “What, on this view will cause the rate of change in nominal income to depart from its permanent level [or trend level path]? Anything that produces a discrepancy between the nominal quantity of money demanded and the quantity supplied, or between the two rates of change of money demanded and money supplied.”

A little over two decades later, in 2003, Friedman popularized that view with his “The Fed´s Thermostat” to explain the “Great Moderation”:

“In essence, the newfound stability was the result of the Fed (and many other Central Banks) stabilizing nominal expenditures. In that case, from the QTM, according to which MV=PY, the Fed managed to offset changes in V with changes in M, keeping nominal expenditures, PY, reasonably stable. Note that PY or its growth rate (p+y), contemplates both inflation and real output growth, so that stabilizing nominal expenditures along a level growth path means stabilizing both inflation and output.”

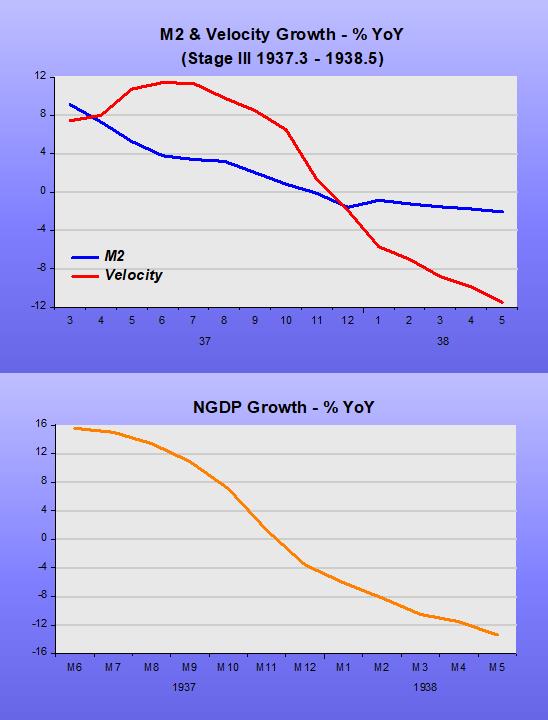

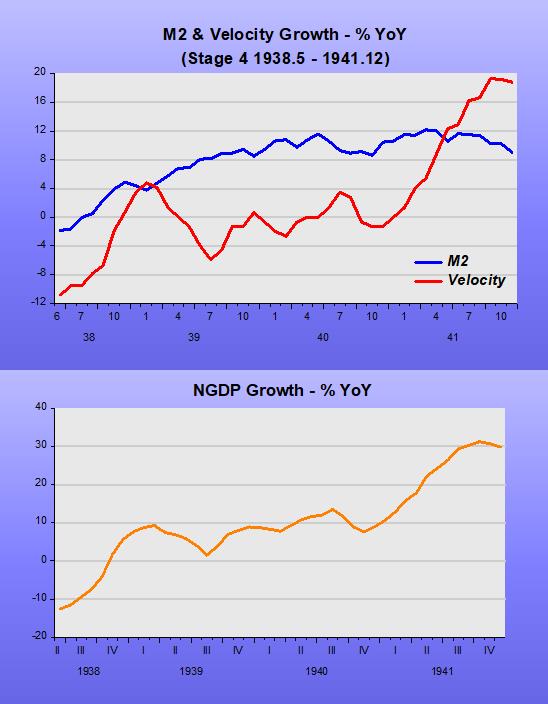

How does that square with the evidence? To illustrate we look at two periods, the “Great Inflation” of the 70s and the “Great Moderation” (1987 – 2005).

During the “Great Inflation”, it seems the Thermostat broke down and the “temperature” kept rising above “normal”. During the “Great Moderation”, it appears the Thermostat worked just fine, keeping the “temperature” close to normal levels at all times.

How does the stability of the trend level path for nominal spending (NGDP) translate to the growth rate view? In the next charts, we observe that during the “Great Inflation” the “temperature” oscillated on a rising trend, while during the “Great Moderation” it was much more stable with no trend.

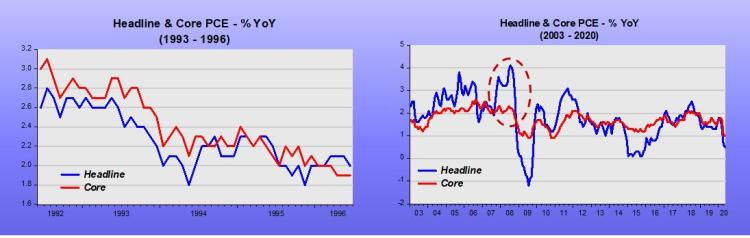

If the Thermostat is working fine, according to Friedman stabilizing nominal expenditures along a level growth path means stabilizing both inflation and output.”

The next charts show that is the observed outcome.

On average, real growth is similar in both periods, while the volatility (standard deviation) of growth is 50% (1.3 vs 2.6) lower.

Note that price & wage controls work like putting a wet cloth on the patient´s forehead to reduce fever, as doctors did in the Middle Ages! As soon as you take away the wet cloth, temperature rises.

An interesting takeaway gleaned from the results following the application of Friedman´s Fed Thermostat, is that the 70s was no “stagflationary decade” as pop culture has it. It was just the “inflationary decade”.

It also shows that comments as the one below are plainly wrong:

“We are right to fear inflation. The 1970s was a colossal disaster and economists still can’t even agree on what exactly went wrong.”

Having understood the meaning and usefulness of “Friedman´s Thermostat”, we can use it to explain what happened after Bernanke took over as Chair in January 2006.

“Dialing down” the economy

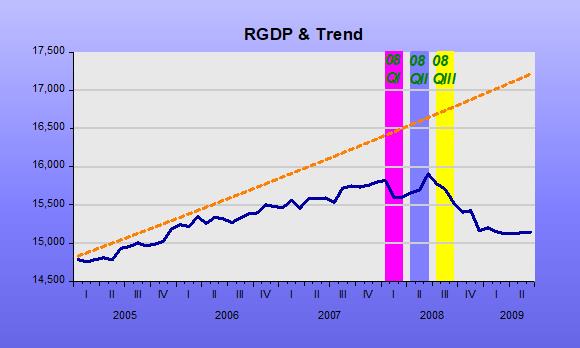

AS the chart shows, when Bernanke began his tenure as Fed Chair, initially he kept nominal spending (NGDP) evolving close to the trend level path. Around mid-2007, he began to worry about the potential inflationary effects of low unemployment (4.4%, below their estimate of the natural rate) and rising oil prices.

At that point, money demand was on a rising trend (falling velocity) due to the uncertainties flowing from the financial sector problems that were brewing (remember the “start date” of the financial crisis was August 07 when two funds from Paribas were closed for redemption) and money supply growth was “timid”. As a result, nominal spending began to fall below trend.

In mid-08, the FOMC became very concerned about inflation. After all, in the 12 months to June 08 oil prices doubled. Bernanke´s summary of that meeting discussions is unequivocal evidence that the Fed´s goal was to “dial down” the Thermostat (or “cool”) the economy!

FOMC Meeting June 2008 (page 97):

“My bottom line is that I think the tail risks on the growth and financial side have moderated. I do think, however, that they remain significant. We cannot ignore them. I’m also becoming concerned about the inflation side, and I think our rhetoric, our statement, and our body language at this point need to reflect that concern. We need to begin to prepare ourselves to respond through policy to the inflation risk; but we need to pick our moment, and we cannot be halfhearted. When the time comes, we need to make that decision and move that way because a halfhearted approach is going to give us the worst of both worlds. It’s going to give us financial stress without any benefits on inflation. So we have a very difficult problem here, and we are going to have to work together cooperatively to achieve what we want to achieve.”

Before that meeting, the fall in nominal spending below trend was likely the result of unintended mistakes in the calibration of the thermostat, in the sense that the increase in money supply failed to fully offset the fall in velocity. During the second half of 2008, however, money supply growth decreased sharply, especially after the Fed introduced IOER in October. That certainly qualifies as “premeditated crime”!

The 2008-09 recession (dubbed “Great”) is more evidence for the relevance of the “Thermostat Framework” spelled out by Friedman. It was the conscious “dialing down” of the thermostat by the Fed, not the house price bust or the associated financial crisis, that caused the deep recession.

The charts below illustrate the impact of the “dialing down of the thermostat” by the Fed.

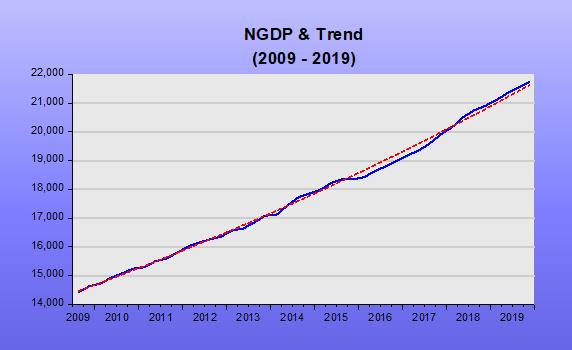

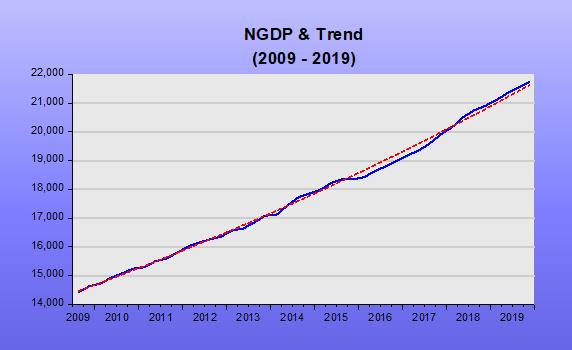

What comes next, however, puts the “Thermostat Analogy” in “all its glory”, in addition to dispelling the notion made popular by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff that this recovery was slow because it followed a financial crisis.

In short, once the economy was “cooled”, the Fed never intended to “warm it up” to the previous trend level path, keeping the thermostat working fine for the lower temperature the Fed desired.

The implications of a well-functioning thermostat are evident in the charts below.

1 Nominal spending is kept stable along a (lower) level path

2 Both real output and inflation are stabilized (also at a lower rate)

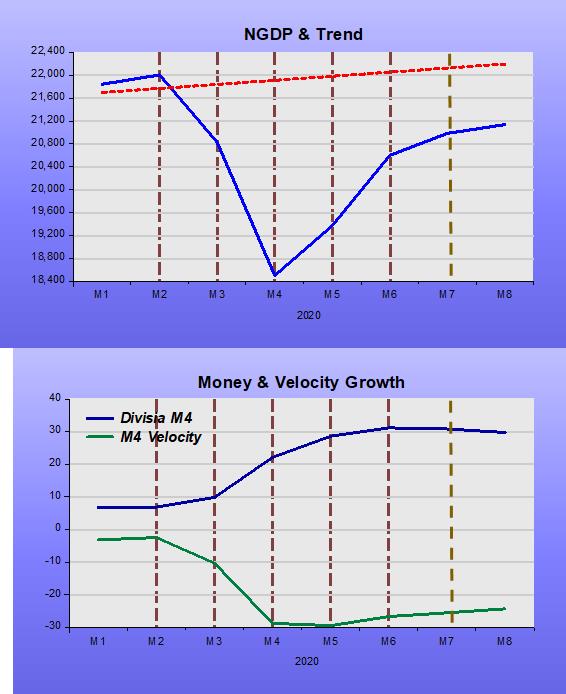

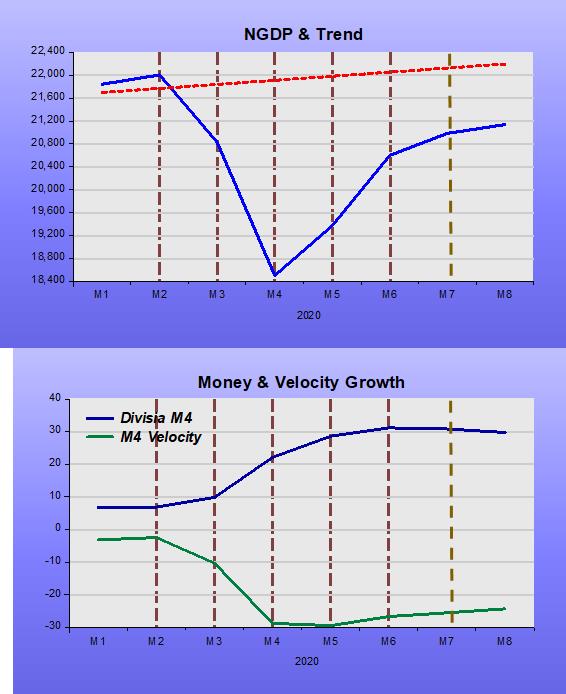

The next chart (which makes use monthly NGDP from Macroeconomic Advisers) shows what happened following the Covid19 “attack”.

This is not like 2008. This time around, the Fed had no hand in the outcome. The virus came out of left field and “crunched” both the supply and demand “armies”, leading to a sudden “drop shock” in nominal spending.

Money demand jumped (velocity tanked). The next chart shows that the Fed reacted in the right way, with a lag, given the surprise attack.

The economy faces a health issue with mammoth economic consequences. The thermostat dialed the temperature down “automatically” and will likely maintain the “cooler temperature” while the virus is “active”. All the Fed can do is work to ensure the temperature does not fall even more. Given the latest data available (May), it appears the Fed is managing to “hold the fort”.

What the inflacionistas worry is with the aftermath, after the virus loses relevance. They argue the massive rise in the money supply observed so far ensures an inflation boom in the future.

As the thermostat analogy indicates, you have to take into account the behavior of velocity (money demand). So far, even with the “Federal Reserve pouring money into the economy at the fastest rate in the past 200 years”, what we observe is disinflation!

How will the Fed behave once the virus loses relevance? Will it set the thermostat at the previous temperature (previous trend level path)? In other words, will it make-up for the losses in nominal spending incurred during the pandemic, or not?

In this post, David Beckworth argues that there is no evidence the Fed plans to undertake a make-up policy, concluding:

“So wherever one looks, make-up policy is not being forecasted. Its absence does not bode well for the recovery and underscores the urgency of the FOMC review of its framework. I really dread repeating the slow recovery of the last decade. So please FOMC, bring this review to a vote and give make-up policy a chance during this crisis.”

After the Great Recession, the Fed chose not to “make-up”. The chart illustrates

What will it be this time around?

If the Fed undertakes a make-up policy, inflation will temporarily rise (just as it temporarily fell when the thermostat was dialed down). The impossible dream I have is that the Fed not only makes up for the virus-induced loss, but also partly for the loss incurred by its misguided policy of 2008!

As always, the inflation obsession will the greatest barrier the Fed will face. No wonder more than 40 years ago James Meade warned that inflation targeting was “dangerous”.

PS Update to the last chart above with data to August 20. The “bad outcome” seems to be transpiring!