In this year´s ASSA Annual Meeting in January, Christina & David Romer (R&R) presented “NBER Business Cycle Dating: Retrospect and Prospect”:

“…Our most substantial proposal is that the NBER continue this evolution by modifying its definition of a recession to emphasize increases in economic slack [Deviations from potential output and/or unemployment] rather than declines in economic activity…”

“…Throughout the paper, we make use of Hamilton´s (1989) Markov switching model as a framework for investigating and assessing the NBER dates. Though judgement will surely never be (and should not be) eliminated from the NBER business cycle dating process, it is useful to see what standard statistical analysis suggests and can contribute.”

On page 32, they move to Application: The implications of a two-regime model using slack for dating US business cycle since 1949:

“We have argued that a two-regime model provides insights into short-run fluctuations. And we have argued for potentially refining the definition of a recession to emphasize large and rapid increases in economic slack rather than declines in economic activity. Here, we combine the two approaches by applying Hamilton´s two-regime model to estimates of slack and exploring the implications for the dating of postwar recessions.”

According to R&R (page 34):

“The largest disagreement between the two regimes estimates using slack and the NBER occurs at the start of the Great Recession. The NBER identifies both 2008Q1 and 2008Q2 as part of the recession (with the peak occurring in 2007Q4), while our estimates (see table 1) put the probability of recession as just 21% in 2008Q1 and 43% in 2008Q2.”

Table 1 Economic Performance going into the Great Recession

| Quarter | NBER Date

In Recession? |

Agreement of 2-Regime Model | Shortfall of GDP from Potential | Unemployment minus Nat Rate |

| 2007Q4 | No | 97% | -0.6% | 0.6% |

| 2008Q1 | Yes | 21% | 4.2% | 0.9% |

| 2008Q2 | Yes | 43% | -0.2% | 1.4% |

| 2008Q3 | Yes | 91% | 3.9% | 2.7% |

It is somewhat confusing! The 2-Regime model only “fully” agrees with the NBER that the economy was in a recession from 200Q3. The GDP gap roams all over the place, while the unemployment gap is increasing consistently over time.

Although R&R suggest the NBER emphasize measures of slack, those measures are very imprecise. This is clear given the CBO systematic revisions of potential output in the chart below.

Since I´m “toying” with dates, I´ll try using the NGDP Level target yardstick to see what it says about the Great Recession. (Useful recent primers on Nominal GDP Level Targeting are David Beckworth and Steve Ambler).

In the years preceding the Great Recession, there were many things happening. There was the oil shock that began in 2004 and gathered force in subsequent years. There was the bursting of the house price bubble that peaked in mid-2006 and, from early 2007, the problems with the financial system began, first affecting mortgage finance houses but soon extending to banks, culminating in the Lehmann fiasco ofSeptember 2008.

The next chart the oil and house price shocks.

The predictable effect of an oil (or supply) shock is to reduce the real growth rate and increase inflation (at least that of the headline variety). The charts indicate that was what happened.

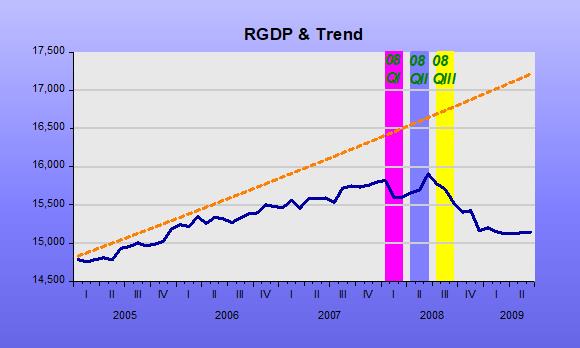

The chart below shows that when real growth fell due to the supply shock, real output (RGDP) dropped below the long-term trend (“potential”?). Does this mean the economy is in a recession? If that were true, the recession would have begun in 2006!

In that situation, how should monetary policy behave? Bernanke was quite aware of this problem. Ten years before, for example, Bernanke et al published “Systematic Monetary Policy and the Effects of Oil Price Shocks”. (1997)

In the conclusion, they state:

“Substantively, our results suggest that an important part of the effect of oil price shocks on the economy results not from the change in oil prices, per se, but from the resulting tightening of monetary policy. This finding may help to explain the apparently large effects of oil price changes found by Hamilton and many others.”

In the chart below, we observe that during his first two years as Chair, Bernanke seems to have “listened to himself” because NGDP remained very close to the target level path all the way through the end of 2007.

With NGDP kept on target, the effects of the supply shock are “optimized”. Headline inflation, as we saw previously will rise, but if there is little or no change in NGDP growth, core measures of inflation will remain contained.

During the first quarter of 2008, NGDP was somewhat constrained. This likely reflects the FOMC´s worries with inflation. RGDP growth dropped further, but during the second quarter of 2008, the Fed seemed to be trying to get NGDP back to trend. RGDP growth responded as expected and core inflation remained subdued.

At that point, June 2008, it appears Bernanke reverted to focus almost singly on inflation, maybe remembering what he had written 81/2 years before in What Happens when Greenspan is gone? (Jan 2000):

“U .S. monetary policy has been remarkably successful during Alan Greenspan’s 121/2 years as Federal Reserve chairman. But although President Clinton yesterday reappointed the 73-year-old Mr. Greenspan to a new term ending in 2004, the chairman will not be around forever. To ensure that monetary policy stays on track after Mr. Greenspan, the Fed should be thinking through its approach to monetary policy now. The Fed needs an approach that consolidates the gains of the Greenspan years and ensures that those successful policies will continue; even if future Fed chairmen are less skillful or less committed to price stability than Mr. Greenspan has been.

We think the best bet lies in a framework known as inflation targeting, which has been employed with great success in recent years by most of the world’s biggest economies, except for Japan. Inflation targeting is a monetary-policy framework that commits the central bank to a forward-looking pursuit of low inflation; the source of the Fed’s current great performance; but also promotes a more open and accountable policy-making process. More transparency and accountability would help keep the Fed on track, and a more open Fed would be good for financial markets and more consistent with our democratic political system.”

This is evident in his summary of the FOMC Meeting June 2008 (page 97), where Bernanke says:

“My bottom line is that I think the tail risks on the growth and financial side have moderated. I do think, however, that they remain significant. We cannot ignore them. I’m also becoming concerned about the inflation side, and I think our rhetoric, our statement, and our body language at this point need to reflect that concern. We need to begin to prepare ourselves to respond through policy to the inflation risk; but we need to pick our moment, and we cannot be halfhearted. When the time comes, we need to make that decision and move that way because a halfhearted approach is going to give us the worst of both worlds. It’s going to give us financial stress without any benefits on inflation. So we have a very difficult problem here, and we are going to have to work together cooperatively to achieve what we want to achieve.”

From that point on, things derailed and a recession becomes clear in the data. It appears the NGDP Level Targeting framework agrees with Hamilton´s 2-regime model that the recession was a fixture of 2008Q3.

If NGDP had not begun to tank in 2008Q3, a recession might, later, have been called before 2008Q3, but it would never have been dubbed “Great”, more likely being short & shallow.

The takeaway, I believe, is that the usual blames placed on the bursting of the house price bubble, which led to the GFC and then to the GR is misplaced. Central banks love that narrative because it makes them the “guys who saved the day” (avoided another GD) when, in fact, they were the main culprits!

PS: The “guiltless” Fed is not a new thing. Back in 1937, John Williams (no relation to the New York Fed namesake), Chief-Economist of the Fed, Board Member and professor at Harvard (so unimpeachable qualifications, said about the 1937 downturn:

“If action is taken now it will be rationalized that, in the event of recovery, the action was what was needed and the System was the cause of the downturn. It makes a bad record and confused thinking. I am convinced that the thing is primarily non-monetary and I would like to see it through on that ground. There is no good reason now for a major depression and that being the case there is a good chance of a non-monetary program working out and I would rather not muddy the record with action that might be misinterpreted.”