Fifty years ago, Milton Friedman published in the JPE “A Monetary Theory of Nominal Income”. I highlight two passages from the paper.

Correspondence of the Monetary Theory of Nominal Income with Experience

I have not before this written down explicitly the particular simplification I have labelled the monetary theory of nominal income—though Meltzer has referred to the theory underlying our Monetary History as a “theory of nominal income” (Meltzer 1965, p. 414). But once written down, it rings the bell, and seems to me to correspond to the broadest framework implicit in much of the work that I and others have done in analyzing monetary experience. It seems also to be consistent with many of our findings.

One finding that we have observed is that the relation between changes in the nominal quantity of money and changes in nominal income is, almost always, closer and more dependable than the relation between changes in real income and the real quantity of money or between changes in the quantity of money per unit of output and changes in prices.

This result has always seemed to me puzzling, since a stable demand function for money with an income elasticity different from unity led us to expect the opposite. Yet the actual finding would be generated by the monetary approach outlined in this paper, with the division between prices and quantities determined by variables not explicitly contained in it.

…On still another level, the approach is consistent with much of the work that Fisher did on interest rates…In particular the approach provides an interpretation of the empirical generalization that high interest rates mean that money has been easy, in the sense of increasing rapidly, and low interest rates that money has been tight, in the sense of increasing slowly, rather than the reverse.

A few pages later in Short-Run Adjustment of Nominal Income, Friedman writes:

For monetary theory, the key question is the process of adjustment to the discrepancy between the nominal quantity of money demanded and the nominal quantity of money supplied…The key insight of the quantity-theory approach is that a discrepancy will be manifested primarily in attempted spending, thence in the rate of change in nominal income.

Put differently, money holders cannot determine the nominal quantity of money, but they can make velocity anything they wish.

What, on this view, will cause the rate of change in nominal income to depart from its permanent value? Anything that produces a discrepancy between the nominal quantity of money demanded and the quantity supplied, or between the two rates of change of money demanded and money supplied.

In symbols, the equation of exchange (in growth form) says that M+V=P+y, with M being money supply growth, V velocity growth, P inflation and y real output growth.

By “ignoring” the division between prices (P) and quantities (y), we are only concerned with aggregate nominal spending growth (or NGDP). In this way, an “appropriate monetary policy” is one that maintains nominal stability (or a stable growth of nominal spending). In other words, an “appropriate monetary policy” is one in which money supply growth offsets changes in velocity to keep NGDP growth stable.

As I´ll show later, it is not just the stable growth rate of NGDP that matters, but also the Level Path of spending along which that growth takes place. That´s the reason Market Monetarists favor NGDP-Level Targeting as the central bank´s framework.

Before going ahead, I think it is useful to put the Monetary Theory of Nominal Income in context.

Traditional versions of monetarism, still followed today, assume velocity is stable. With that assumption, the equation of exchange in growth form is written (to an approximation) as M=P+y or M-P=y so that statements such as:

“In a large body of work with a number of colleagues Friedman demonstrated that inflation was “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, meaning that it arose over extended periods only when the quantity of money increased more rapidly than the quantity of goods and services.”

Are not valid.

When Friedman concluded that money holders cannot determine the nominal quantity of money, but they can make velocity anything they wish, he was led to the view that the relation between changes in the nominal quantity of money and changes in nominal income is, almost always, closer and more dependable than the relation between changes in real income and the real quantity of money or between changes in the quantity of money per unit of output and changes in prices.

The other contender, New Keynesianism, is a way of analyzing the economy with a mere three equations, none of which refers to the quantity of money. A “two line summary” would be:

In New Keynesian analysis, monetary policy (interest rate policy) determines real GDP, which in turn determines inflation via a Phillips curve.

[Notes: In what follows, for the money supply, I consider the Divisia M4 index, a very broad measure of the money supply. The data are available at the Center for Financial Stability and a good discussion of the indices construction and usefulness for monetary policy is “Getting it Wrong”, by William Barnett. For inflation, I consider the headline PCE in order to take account of supply shocks such as oil prices. For unemployment, I use the Core version, which does not consider “temporary layoffs”. That´s a fixture of the “Covid19 pandemic”, with the two measures, core & headline unemployment, showing little difference for all other periods. For details, see here.]

To check if the Monetary Theory of Nominal Income stands up to scrutiny, I analyze several periods over the last 30 years. For each period, the top chart shows the “outcome” of M+V=P+y(NGDP), while the bottom chart shows what happened to “pieces” of the economy; RGDP(y), Inflation(P) and unemployment.

The first chart covers the 1990s.

Monetary policy was quite good. In the top chart, we observe nominal income (NGDP) growth was stable, with some sign of instability occurring when money supply growth did not adequately offset velocity changes.

In the bottom chart, RGDP growth “mimicked” nominal income growth. The unemployment rate fell almost continuously and inflation remained low (close to “target”). Towards the end of the period, inflation falls. That´s due to the occurrence of two positive supply shocks; the fall in oil prices following the Asia crisis 0f 1997/98 and the rise in productivity growth from 1997.

It appears that a monetary policy geared to keeping NGDP growth on a stable path gives out “good results”.

The second chart illustrates the more “confusing” follow-up period.

When the Asia crisis and Russia crisis (remember LTCM?) were “solved”, oil prices began to rise. In 1999 and for most of 2000, monetary policy kept NGDP growth stable. For that interval, RGDP growth remained stable and robust and unemployment still fell somewhat.

The combination of low unemployment and rising inflation signaled red flags to the Fed. Velocity fell significantly while money supply growth was “timid” in offsetting it. NGDP growth fell strongly, from about 5.5% to close to 2%. The effect on RGDP growth of the negative supply shock was magnified and unemployment rose.

With monetary policy succeeding in stabilizing NGDP growth (around 4%), unemployment remains higher but stable. Around mid-2003, the Fed becomes more expansionary adopting “forward guidance”. Velocity rises (and money supply growth does not offset it). NGDP growth climbs to the 5% range, RGDP growth picks up and unemployment begins to fall. The end of the oil surge and the recession of 2001 had brought inflation down, and it remained low & stable after that.

The next chart covers the last years of the Great Moderation”, the last two years of Greenspan´s and the first months of Bernanke at the Fed´s helm

Contrary to many that view this period as an example of “bad” (expansionary) monetary policy, I believe monetary policy was close to “perfect”, especially given the fact that it coincides with the first leg of a persistent negative oil shock that extended to mid-2008.

The Dynamic AS/AD model tells us that, because of a negative supply shock, real growth falls and inflation rises. That´s exactly what happens as observed in the lower chart. In the top chart, however, monetary policy remains geared to providing nominal stability (stable NGDP growth).

With that, unemployment remains on a downtrend. I bet Claudia Sahm felt excited by that outcome shortly before she joined the Fed in 2007.

Unfortunately, in early 2006, Bernanke took over from Greenspan, and Bernanke has a “visceral” fear of inflation. The next chart shows that soon after, NGDP growth drops a notch and unemployment stops falling.

With inflation rising and unemployment low, in early 2008 the Fed tightens monetary policy (reflected in monetary expansion falling short of the fall in velocity). Unemployment begins to increase and the fall in RGDP growth is magnified.

At the closing of this period, it´s almost as if the Fed realizes its mistake and loosens monetary policy somewhat. The unemployment rate, however, does not have time to react because the Fed, scarred of inflation due to oil price increases tightens massively, as seen in the chart below.

The evidence for that comes from Bernanke himself:

Bernanke June 2008 FOMC Meeting (page 97):

“I’m also becoming concerned about the inflation side, and I think our rhetoric, our statement, and our body language at this point need to reflect that concern. We need to begin to prepare ourselves to respond through policy to the inflation risk; but we need to pick our moment, and we cannot be halfhearted.”

The Great Recession of 2008/09 is on. NGDP growth and RGDP growth sink while inflation goes from 4% to -1% and unemployment shoots up from 6% to 10%.

The next chart, in my mind, is the most compelling evidence for the monetary theory of nominal income approach.

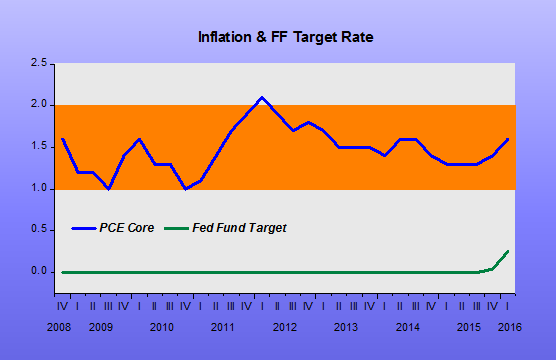

By early 2010, NGDP growth was back to 4% YoY, with NGDP growth averaging 4% over the next 10 years. That was not due to interest rates remaining at the ZLB until December 2015, but to the fact that money supply growth adequately offset velocity changes to maintain stable NGDP growth.

The bottom chart shows that with nominal stability consolidated, the unemployment rate enters a long period of decline going from 10% to less than 4% before the pandemic began. RGDP growth was very stable around the average of 2.2% and headline inflation remained low and stable, averaging 1.6%.

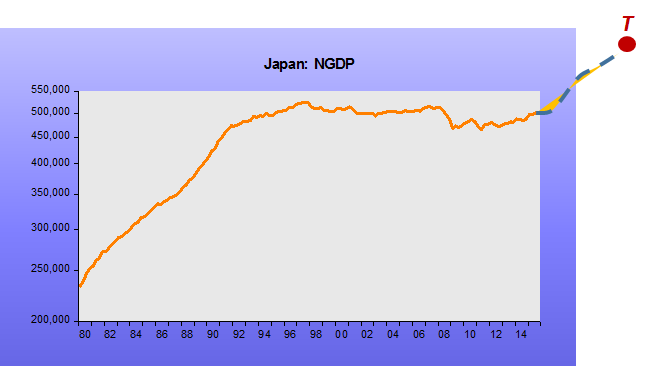

But, and there´s always a “but”, those 10 years comprise a vivid example of the importance of the level path along which nominal stability occurs.

The chart below illustrates, showing that after the Great Recession, the economy evolved very stably along a much lower nominal income level.

Over the years, the rate of unemployment has become not just a gauge of the health of the labor market but the most common yardstick policymakers use to assess the health of the economy as a whole.

Some have argued that the historically low rate of unemployment attained is testament to the strength of the economy. Unfortunately, that´s not so. When you look at the determinants of the unemployment rate, the employment population ratio and labor force participation, you see that the post Great Recession economy is much “weaker” than the pre GR economy.

Labor force participation provides a measure of the “excitement” conveyed by the labor market. The “low” level of nominal income has “muted” that “excitement”.

Almost one year ago, the pandemic hit. The next chart shows the steep & deep fall in velocity (remember, money holders can make velocity whatever they wish). This time, monetary policy reacted quickly to stop the bleeding.

As the next chart shows, however, monetary policy still falls short of what´s needed, so that the level of NGDP remains below, and even distancing itself from the already low level that prevailed after the Great Recession.

As the pandemic withers with mass vaccination, the demand for money will fall (velocity will rise). The Fed will have to offset this rise in velocity in order to stabilize the growth of nominal income (NGDP). It will also have to choose a level path, hopefully higher than the one it travelled for the 10 years to early 2020!

As the NGDP growth rises to reach a higher-level path, some of that rise could reflect (temporarily) higher inflation. Despite the Fed having adopted Average Inflation Targeting (AIT), a higher inflation will most likely cause “nervousness” at the Fed. That´s probably why, more than 10 years ago, Scott Sumner wrote:

I don’t propose to abolish the phenomenon of inflation, but rather the concept of inflation. And to be more precise, price inflation, which is what almost everyone means by the term. I want it stripped from our macroeconomic theories, removed from our textbooks, banished into the dustbin of discarded mental constructs.