In 1995, while a managing director of the IMF, Stanley Fischer wrote an essay titled: “Modern Central Banking”, where he ardently defends “Inflation Targeting” (The NBER version is here):

…The issue of a target price level (PLT) versus target inflation rate (IT) nonetheless remains. Compare the goal of being close to a target price level that is growing at 2% per annum from a given date, say 1995, with the goal of achieving a 2% inflation rate each year from 1995 on.

With a target price path (PLT), the monetary authority attempts to offset past errors, thus creating more uncertainty about short-term inflation rates than with an inflation target (IT). The gain is more certainty about the long-term price level.

My present view is that the inflation target with its greater short-term inflation rate certainty is preferable, despite its greater long-term price level uncertainty.

I thought that view was “narrow-minded”, in particular given that important firm and individual decisions tend to be longer term ones. Does Fischer still hold those views from 20 years ago?

By 2011 he had come to favor a flexible IT regime:

“A central bank should aim to maintain price stability and support other goals, particularly growth and employment. So long as medium-term price stability — over the course of a year or two or even three — is preserved.”

Price stability means 2% inflation. But for at least six years inflation (as measured by PCE Core prices) has been well below target except for a fleeting moment in early 2012, coinciding with the moment the 2% target was made official. Barring people like Bullard who think the “Core is rotten”, most people think core prices provide a better indication of the inflation trend. (The chart indicates how fickle the Fed would be if it targeted headline inflation at 2%!)

So by Fischer´s own definition we haven´t experienced “price stability” for several years, implying a lot of uncertainty about “short-term inflation rate certainty”.

In fact, “long-term price level uncertainty has been lower than short-term inflation uncertainty”, especially if you associate the price level with the core measure of the PCE.

As the panel below shows, core prices evolved very close to trend until 2012, after which they fall a little short. The headline price level was impacted by the persistent oil shocks during 2003-08. More recently, the negative oil shocks have brought it back to trend. Meanwhile, core inflation has spent most of the time below the target (initially implicit) level.

From a PLT perspective, the Fed is doing OK. From an IT perspective, it is doing a pretty awful job. But note that trying to “correct” inflation (bring it to target) will likely “disturb” the PLT (at least the headline price level). But the Fed doesn´t target the price level!

In 2008 the Fed botched the job because it became “afraid” of the increase in headline inflation that was rising on the heels of oil prices. That shows the main deficiency of both IT and PLT. Both are sensitive to real or supply shocks. Since the Core measure of the price level is much less sensitive to supply shocks, the fall in the core price level below trend over the past few years is an indication, contrary to FOMC conventional wisdom, that the drop in inflation is due to more than recently falling oil prices! Would that be related to a monetary policy that is implicitly tight?

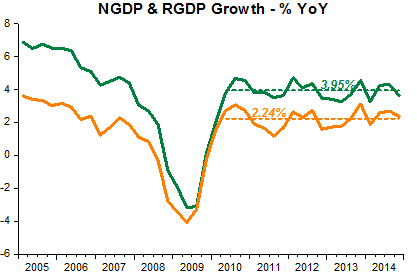

On that score, the panel also shows that the major factor behind both the depth of the recession and the weak recovery was the Fed letting nominal spending drop way below trend and then not allowing it to climb back towards trend, i.e. keeping monetary policy too tight!

The NGDP & Trend chart is also evidence that the prevalent view that monetary policy was “too easy” in 2002-05 is misguided. With the FF rate at 1%, in August 2003 the FOMC decided to undertake forward guidance. All measures of inflation were below the target, and so was the NGDP level. It was effective in bringing both NGDP and core inflation back to target (headline was impacted by oil, and that shouldn´t concern the stance of monetary policy).

Bernanke took over with a “clean slate”! And proceeded to botch the job!

Unfortunately, those responsible for monetary policy simply won´t recognize the need for an overhaul in how monetary policy is conducted. Simply “endowing” the inflation target with more flexibility, imposing interest rate rules (aka “Taylor-type” rules) or even adopting a PLT won´t cut it. One of the consequences of this “hard-headedness” will be increasing claims for the use of distortionary fiscal policies (“stimulus”).

Unfortunately as he has made abundantly clear over the years, Stanley Fischer is quite against it, although he left a door open in a 2011 speech called “Central Bank Lessons from the Global Crisis”:

During and after the Great Depression, many central bankers and economists concluded that monetary policy could not be used to stimulate economic activity in a situation in which the interest rate was essentially zero, as it was in the United States during the 1930s – a situation that later became known as the liquidity trap. In the United States it was also a situation in which the financial system was grievously damaged. It was only in 1963, with the publication of Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History of the UnitedStates that the profession as a whole1 began to accept the contrary view, that “The contraction is in fact a testimonial to the importance of monetary forces.”

In this lecture, I present preliminary lessons – nine of them – for monetary and financial policy from the Great Recession. I do this with some trepidation, since it is possible that there will later be a tenth lesson: that given that it took fifty years for the profession to develop its current understanding of the monetary policy transmission mechanism during the Great Depression, just two years after the Lehmann Brothers bankruptcy is too early to be drawing even preliminary lessons from the Great Recession. But let me join the crowd and begin doing so.

…………………………………………………………………………..

The ninth:

In a crisis, central bankers (and no doubt other policymakers) will often find themselves implementing policy actions that they never thought they would have to undertake – and these are frequently policy actions that they would prefer not to have to undertake. Hence, some final advice for central bankers :

Never say never