In “A Feature Not a Bug in the Policy Rules Bill” John Taylor writes:

In his opening line of questions for Janet Yellen at the Senate Banking Committee today, Senator Richard Shelby asked about the use of monetary policy rules and the Taylor Rule, apparently referring to the recent policy rules bill (Section 2 of HR 5018) that would require the Fed to report its strategy or rule for policy. The headline-grabbing first sentence of Janet Yellen’s response was about not wanting to “chain” the FOMC to a rule, and it did get a lot of attention (including many real time tweets). But it was the rest of her response that really focused on the Senator’s question. Here is a transcript from C-Span (minute 28:39).

SENATOR SHELBY: YOU HAVE OPINED ON THE USE OF MONETARY POLICY RULES SUCH AS THE TAYLOR RULE, WHICH WOULD PROVIDE THE FED WITH A SYSTEMATIC WAY TO CONDUCT POLICY IN RESPONSE TO CHANGES IN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS. I BELIEVE IT WOULD ALSO GIVE YOU — GIVE THE PUBLIC A GREATER UNDERSTANDING OF, AND PERHAPS CONFIDENCE IN, THE FED’S STRATEGY. YOU’VE STATED, AND I’LL QUOTE, RULES OF THE GENERAL SORT PROPOSED BY TAYLOR CAPTURE WELL OUR STATUTORY MANDATE TO PROMOTE MAXIMUM EMPLOYMENT AND PRICE STABILITY. YOU HAVE EXPRESSED CONCERNS, HOWEVER, OVER THE EFFECTIVENESS OF SUCH RULES IN TIMES OF ECONOMIC STRESS. WOULD YOU SUPPORT THE USE OF A MONETARY POLICY RULE OF THE FED’S CHOOSING IF THE FED HAD DISCRETION TO MODIFY IT IN TIMES OF ECONOMIC DISRUPTION? >>

CHAIR YELLEN: I’M NOT A PROPONENT OF CHAINING THE FEDERAL OPEN MARKET COMMITTEE IN ITS DECISION MAKING TO ANY RULE WHATSOEVER. BUT MONETARY POLICY NEEDS TO TAKE ACCOUNT OF A WIDE RANGE OF FACTORS SOME OF WHICH ARE UNUSUAL AND REQUIRE SPECIAL ATTENTION, AND THAT’S TRUE EVEN OUTSIDE TIMES OF FINANCIAL CRISIS. IN HIS ORIGINAL PAPER ON THIS TOPIC, JOHN TAYLOR HIMSELF POINTED TO CONDITIONS SUCH AS THE 1987 STOCK MARKET CRASH THAT WOULD HAVE REQUIRED A DIFFERENT RESPONSE. I WOULD SAY THAT IT IS USEFUL FOR US TO CONSULT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF RULES OF THE TAYLOR TYPE, AND OTHERS, AND WE DO SO ROUTINELY, AND THEY ARE AN IMPORTANT INPUT INTO WHAT ULTIMATELY IS A DECISION THAT REQUIRES SOUND JUDGMENT

Back to Taylor:

Note how Janet Yellen refers to my 1993 paper where I pointed to the 1987 stock market break as a case where there was a deviation from the Taylor rule. However, this example is really a illustration of how the policy rule legislation would work effectively rather than a critique of the legislation. To see this, take a look at this chart from my original paper:

Notice how the funds rate was cut in 1987 while the policy rule setting kept rising. This is the deviation that Janet Yellen was referring to. It is actually quite small and temporary, but in any case the Fed could easily take such an action and stay within the terms of the policy rules bill. The Fed chair would simply explain the explicit reason for the deviation as required in the legislation. I can’t imagine the case would be difficult to make given the size of the shock unless for some reason the deviation continued long after the shock.

This example illustrates a feature not a bug in the bill.

Understandably, John Taylor is an unconditional fan of his namesake rule. Interestingly Yellen says that the Fed shouldn´t “be chained to any rule whatsoever”. Why? Because monetary policy requires “sound judgment”? And rules won´t provide that?

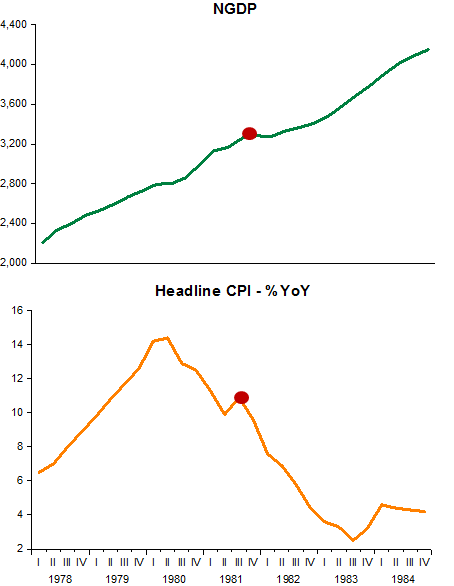

Maybe that´s a problem associated with “instrument rules” like Taylor-type rules, which give out the “desired” setting for the interest rate instrument (the FF target rate in the case of the US). What if the central bank, instead of an “instrument rule” adopted a “target rule”? For concreteness, let´s assume the Fed had adopted (maybe implicitly) a NGDP level target as it´s rule for monetary policy.

The charts compare and contrast the interest rate “policy rule” and the NGDP level target rule (where the “target (trend) level” is the “Great Moderation” (1987-05) trend). In this comparison, the actual setting of the Federal Funds (FF) rate is “right or wrong” depending on, not if it agrees with the setting “suggested” by the instrument rule, but if it is the rate that keeps NGDP close to the target path; and in case there is a deviation from the path, if the (re)setting drives NGDP back to the target.

For the “instrument rule”, I use the Mankiw version of the Taylor rule. The Mankiw version is simpler because it doesn´t require the estimation of an output gap and doesn´t state an inflation target rate (which the Fed didn´t have any way until January 2012).

The first chart shows John Taylor´s chart from his original 1993 paper. Note that it is qualitative (even if not exactly quantitative) similar to the “policy rule” obtained with the Mankiw rule.

During this period (1987 – 1992) monetary policy was “quite good”, in the sense of keeping NGDP close to the “target path”. Actually, when the Fed reduced the FF rate at the time of the stock market crash, it turned monetary policy a bit too expansionary, given NGDP went a bit above trend.

The next period covers 1993 – 1997. This is the core period of the “Great Moderation”. At the end of 1992, the FF rate had been reduced to 3%, a level which was maintained throughout 1993. According to the “policy rule” this was “too low”. With respect to the “target rule”, the FF rate was “just right”.

All through those years, NGDP remained very close to the “target path”, although the FF rate at times differed significantly from the “policy rule”.

The next period, 1998 – 2003.II is pretty damaging to the “policy rule” advocates. Taylor likes to say that the 2002 – 2005 period was one of “rates too low for too long” (having responsibility for the crash that came later).

What the chart tells us, however, is very different. The FF rate was too low in 1998 – 99. At this time, the Fed reacted to the Russia crisis (and the LTCM affair). Monetary policy loosened up at the same time that the economy was being buffeted by a positive productivity shock.

The monetary tightening that followed was a bit too strong because NGDP dropped below trend. The downward adjustment of the FF rate was correct in the sense that it stopped NGDP from falling lower, and by mid-2002 it began to recover. I wonder how much more grief the economy would have been subjected to if the “policy rule” had been followed.

The 2003.III – 2005 period is the second half of Taylor´s “too low for too long”. In the FOMC meeting of August 2003, the Fed adopted “forward guidance” (FG) (first it was “rates will remain low for a considerable period” followed by “will be patient to reduce accommodation, and finally “rates will rise at a measured pace”). The fact is that FG helped push NGDP back to trend. Maybe the “pace was too measured”, but the fact is that by the time he handed the Fed to Bernanke, NGDP was square back on trend.

If the “policy rule” had been closely adhered to, the “Great Recession” would likely have happened sooner!

And now (“the end is near…”) we come to see how the Fed botched monetary policy (likely due to Bernanke´s preferred inflation targeting monetary policy regime).

The FF rate remained at the high level it had reached at the end of the “measured pace story”. At the end of 2006, aggregate demand (NGDP) began to deviate, at first slowly, below the trend level. The FF rate remained put (notice that although too high, the “rule rate” changed direction). The FOMC was not comfortable with the “elevated” price of oil and kept hammering on the risks of inflation expectations becoming un-anchored (see the late 2007-08 FOMC transcripts).

Despite the reduction in the FF rate, monetary policy was being tightened! And the “Great Recession” was invited in! Maybe there would have been a “Second Great Depression” if the “policy rate” had been followed closely.

Moral of the story. Yellen and the Fed do not have “infinite degrees of freedom”, hidden under the umbrella of “sound judgment”. They would do well to set a “target rule”