In his first ‘free speech’ earlier this month Bernanke lied (though he was not under oath):

(Reuters) – Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said the U.S. central bank could have done more to fight the country’s financial crisis and that he struggled to find the right way to communicate with markets.

“We could have done some things on the margin to mitigate somewhat the crisis,” Bernanke, 60, said on Tuesday in his first public speaking engagement since he stepped down in January after eight years heading the Fed.

“Although we have been very aggressive(!), I think on the monetary policy front we could have been even more aggressive.”

Let´s see (via John Taylor):

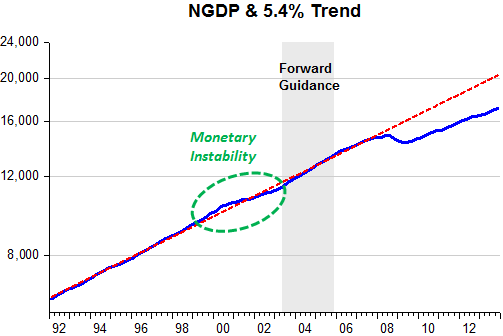

Dec 2008: “Exceptionally low levels…for some time…”

Mar 2009: “…for an extended period…”

Aug 2011: “…at least through mid-2013…”

Jan 2012: “…late 2014…”

Sep 2012: “…through mid-2015…”

Dec 2012: “…at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6 ½ percent…”

And then in May 2013 he thought that it was appropriate to signal the start of ‘the taper’! Was that viewed as “aggressive” monetary policy? Maybe an “aggressive tightening”! This is the story told by medium and long term inflation expectations. See how they plunge when the “taper talk” began.

Being an inflation targeter is in Bernanke´s DNA. In January 2012, almost four years after NGDP crashed, Bernanke realized his “life-long dream” and got his preferred 2% inflation target become official policy. To me that shows he didn´t think his inflation obsession in 2008 had any influence in the crisis.

After all, he was the editor of the book that helped disseminate the idea. And as far back as January 2000, while still an academic, he laid down his blueprint for the Fed in “What happens when Greenspan is gone?”

U .S. monetary policy has been remarkably successful during Alan Greenspan’s 121/2 years as Federal Reserve chairman. But although President Clinton yesterday reappointed the 73-year-old Mr. Greenspan to a new term ending in 2004, the chairman will not be around forever. To ensure that monetary policy stays on track after Mr. Greenspan, the Fed should be thinking through its approach to monetary policy now. The Fed needs an approach that consolidates the gains of the Greenspan years and ensures that those successful policies will continue; even if future Fed chairmen are less skillful or less committed to price stability than Mr. Greenspan has been.

We think the best bet lies in a framework known as inflation targeting, which has been employed with great success in recent years by most of the world’s biggest economies, except for Japan. Inflation targeting is a monetary-policy framework that commits the central bank to a forward-looking pursuit of low inflation; the source of the Fed’s current great performance; but also promotes a more open and accountable policy-making process. More transparency and accountability would help keep the Fed on track, and a more open Fed would be good for financial markets and more consistent with our democratic political system.

Now Yellen´s turn:

March 2014: “…the language that we use in this statement is considerable, period…. this is the kind of term it’s hard to define, but, you know, it probably means something on the order of around six months or that type of thing…”

As Hilsenrath notes:

Wall Street is abuzz about rising interest rate projections released by the Federal Reserve Wednesday in a supplement to its official policy statement. A careful reading of these scatter plot projections suggests the central bank’s camp of policy “doves” shifted its interest rate views slightly upward in March.

As Jim Pethokoukis has transcribed:

In the end, the Fed has eliminated the 6.5% trigger that wasn’t a trigger. Yellen has replaced it with a laundry list of things that matter with no objectives for any of them. We are back in the land of discretion. Rules did not work, because the Fed set the wrong rules. But the policy objective of price stability- and that means 2% inflation- is still there and still not being met. Moreover, the Fed is willing to hike rates and slow progress toward the 2% goal long before we get there, an act that slows the drop in the already too-high rate of unemployment.

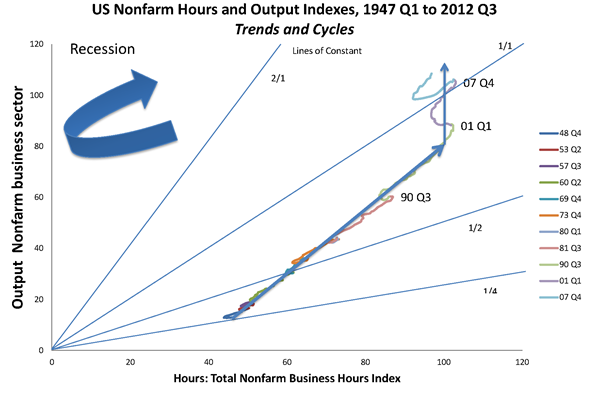

The Phillips Curve is in Yellen´s DNA. Travel back to the September 1996 FOMC meeting:

MS. YELLEN. Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I can support your proposal to adopt an unchanged policy with an asymmetric directive and to continue to evaluate incoming data as it bears both on the degree of momentum in demand and the inflationary pressures latent in the current environment. But I find myself very close to the margin and would also have been quite willing to support an upward adjustment of 25 basis points today, had you proposed that. I can support your proposal because, for the reasons that I outlined earlier and you explained in fascinating detail, this is an unusual episode. I believe we are still at quite an early stage of an inflationary uptick, if indeed this turns out to be one. I also agree that with demand moderating and current inflation stable or falling, we may end up deciding that it is unnecessary to move the funds rate upward.

But having said that, I believe that a very solid case can also be made for raising the federal funds rate at least modestly, by 25 basis points, on the grounds that the unemployment rate has notched down further, the decline in labor market slack is palpable, and the odds of a rise in the inflation rate have increased, whatever the level of the NAIRU and the associated level of those odds. I believe I am echoing Governor Meyer in saying that I favor a policy approach in which, absent clear contra-indications, our policy instrument would be routinely adjusted in response to changing pressures on resources and movements in actual inflation.

That pretty well describes her thinking-mode almost 20 years later!

Her “partner” Laurence Meyer gave a speech a few months later, in April 1997, that leaves no doubt about where they stood (and where she still stands):

Let me remind you at the outset of the framework I have been using to explain the challenge facing monetary policy in the current environment of healthy growth and high levels of resource utilization. The risk of higher inflation in this environment has two dimensions. First, there is the risk that current utilization rates are already so high that inflation will gradually increase over time. Second, there is the risk that the growth in output will be above trend going forward, implying that utilization rates will rise from their already high level, compounding the risk of higher inflation.

The recent Federal Reserve policy action was clearly a preemptive one. This means that it was undertaken not in response to where the economy and inflation were at the time of the policy change, but in response to where the economy and inflation were projected to be in the future, absent a policy change. Such policy action necessarily involves a forecast and such a forecast typically is grounded in some model that relates growth, unemployment, wage change and inflation, among other variables. So let me be specific about the causal structure of the model that underpins my judgment with respect to appropriate monetary policy action.

I am a strong and unapologetic proponent of the Phillips Curve and the NAIRU concept. Fundamentally, the NAIRU framework involves two principles. First, the proximate source of an increase in inflation is excess demand in labor and/or product markets. In the labor market, this excess demand gap is often expressed in this model as the difference between the prevailing unemployment rate and NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. Second, once an excess demand gap opens up, inflation increases indefinitely and progressively until the excess demand gap is closed, and then stabilizes at the higher level until cumulative excess supply gaps reverse the process.

The chart illustrates the inflation-unemployment combination back then and today.

In short, there has been no ‘quality improvement’ in monetary management!