Narayana Kocherlakota writes “The Fed Has Some Explaining to Do”:

My forecast is that the Fed will remain reluctant to raise rates until inflationary pressures are much stronger, at which point it will feel compelled to move at a faster pace than four times per year. This is similar to Chicago Fed President Charles Evans’s suggestion that the central bank should wait to raise rates until core inflation reaches 2 percent. If prices start rising at that rate, the Fed will be right to put a lot more weight on inflationary concerns than on downside risks.

Charles Evans’ suggestion has been practiced in the past.

Back in mid-2003, when inflation was far below 2%, the Fed adopted forward guidance (“FG”). In the Minutes of the August 2003 meeting we read:

The Committee judges that, on balance, the risk of inflation becoming undesirably low is likely to be the predominant concern for the foreseeable future. In these circumstances, the Committee believes that policy accommodation can be maintained for a considerable period.

In January 2004, the message changed to:

With inflation quite low and resource use slack, the Committee believes that it can be patient in removing its policy accommodation.

In May 2004, in the meeting before the first rate hike, the message became:

With underlying inflation still expected to be relatively low, the Committee believes that policy accommodation can be removed at a pace that is likely to be measured.

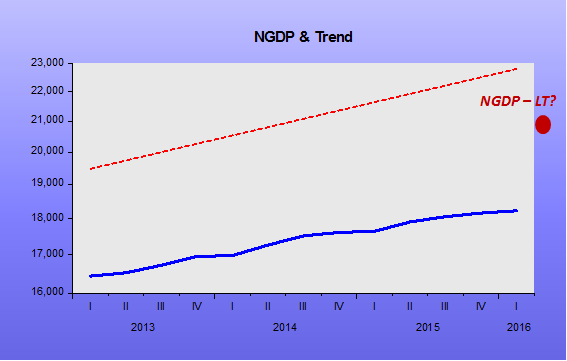

The chart illustrates the period:

The FF Target rate started moving up when core inflation reached 2%, just like Charles Evans suggests at present.

However, note that at the time, NGDP was somewhat below the trend level path. The chart indicates that forward guidance was sufficient to take it back to trend, with core inflation at 2%

Unfortunately, at present, the environment is very different. Today, NGDP is way below the original trend level, in which case, even if (big if) inflation is brought closer to 2%, the level of nominal spending will still remain far below any reasonable trend path.

To “ignite” the economy, and lift it from the depressed state it´s in, the best alternative is not to keep “fiddling” with interest rates, but to change the target to an NGDP Level target.