The Fed´s new Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy is all about “making-up”; be it about inflation below target or unemployment shortfalls.

The Fed is not changing its ultimate mandate, which is to balance price stability with maximum employment. However, it has announced that it will no longer preemptively slow down the economy if the labor market begins to look tight and it will treat its 2% inflation target as an average.

Why the new statement? According to Lael Brainard, since the end of the “Great Recession” the US economy has been in a “new normal”. Three things characterize “new”:

- The equilibrium interest rate has fallen to low levels, which implies a large decline in how much we can cut interest rates to support the economy.

- Underlying trend inflation appears to be somewhat below the Committee’s 2 percent objective, according to various statistical filters.

- The sensitivity of price inflation to labor market tightness is very low relative to earlier decades, which is what economists mean when they say that the Phillips curve is flat.

How does that compare with the “old normal” (Great Moderation)?

- The equilibrium or neutral interest rate was never a concern. It averaged 2.3%, close to the 2% John Taylor pinned it at in his 1993 Taylor-rule. Since the end of the GR it has averaged 0.3%.

- In the “old normal”, core PCE inflation averaged 2.1%, almost exactly the 2% that was the implicit target at the time. During the “new normal”, it has averaged 1.6%.

- The “low sensitivity of price inflation to labor market tightness was already low relative to previous decades. For example, speaking in 2007, Bernanke 2007 said:

“…many studies of the conventional Phillips curve find that the sensitivity of inflation to activity indicators is lower today than in the past (that is, the Phillips curve appears to have become flatter);1 and that the long-run effect on inflation of “supply shocks,” such as changes in the price of oil, also appears to be lower than in the past (Hooker, 2002).

The “new normal” mindset leads to comments such as these:

“Monetary policy is really good for playing defense,” said Adam S. Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “But not for playing offense.”

“If the Fed is relatively weak in its ability to end recessions, why do its actions get so much attention during times of economic crisis? Mostly because the actions of Congress (dominated for the past decade by the Republican caucus in the Senate) have been either too weak or outright damaging during these crises. For example, in the weak recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009, austerity imposed by a Republican-led Congress throttled growth, even as historically aggressive actions by the Fed tried (only partly successful) to counter this fiscal drag.”

That´s interesting because during the “Great Inflation” of the 1970s, Fed Chair Arthur burns thought the Fed could not play defense, but under the right circumstances, it could be good at playing offense!

“Another deficiency in the formulation of stabilization policies in the United States has been our tendency to rely too heavily on monetary restriction as a device to curb inflation…. severely restrictive monetary policies distort the structure of production. General monetary controls… have highly uneven effects on different sectors of the economy.”

Burns did not consider monetary policy to be the driving force behind inflation. He believed that inflation emanated primarily from an inflationary psychology produced by a lack of discipline in government fiscal policy and from private monopoly power, especially of labor unions. It followed that if government would intervene directly in private markets to restrain price increases, the Federal Reserve could pursue a stimulative monetary policy without exacerbating inflation.

The new and old normal share characteristics:

- In both cases, NGDP growth, RGDP growth and inflation were stable, albeit at lower rates in the new normal

- Phillips Curve thinking was the wrong mindset in both cases. It was a very costly mistake in both instances.

The question that naturally comes up is “what led us from one state to the other”?

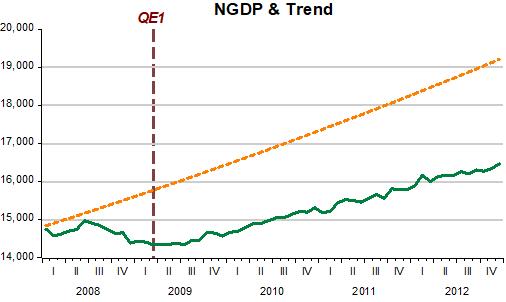

The two states are illustrated by the behavior of aggregate nominal spending (NGDP).

In both, NGDP is stable along a level path. We can infer that those paths and associated growth rates were chosen, (were not accidental). The same goes for the inflation rate that averaged a stable 2.1% in the old normal and 1.6% in the new.

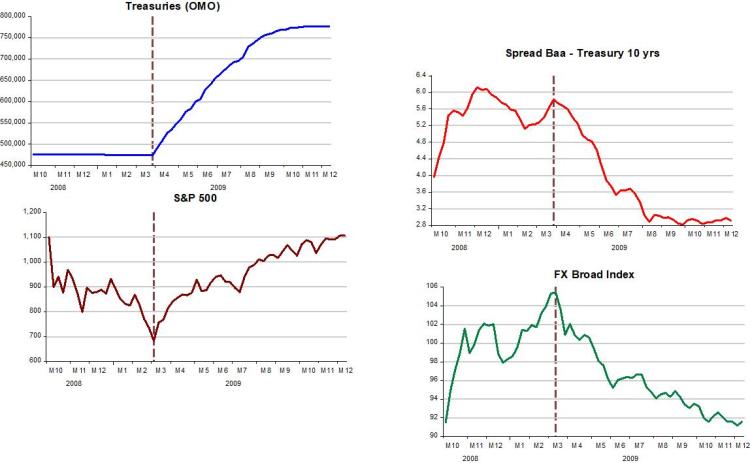

The transition from one state to the other took place in 2008-09. In the chart below, we see that both NGDP and money supply growth tanked and inflation shifted down from 2% to 1%.

The Fed never tried to make up for the drop in NGDP and inflation, resuming expansion along a lower level path and lower rates.

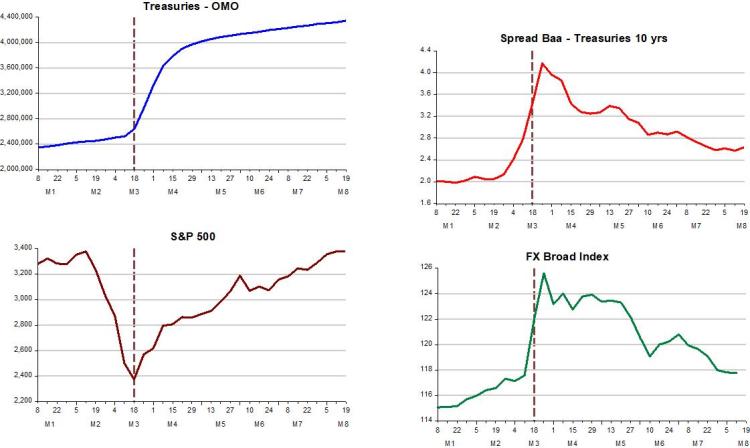

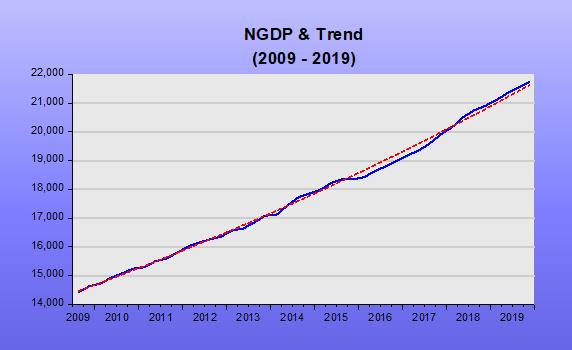

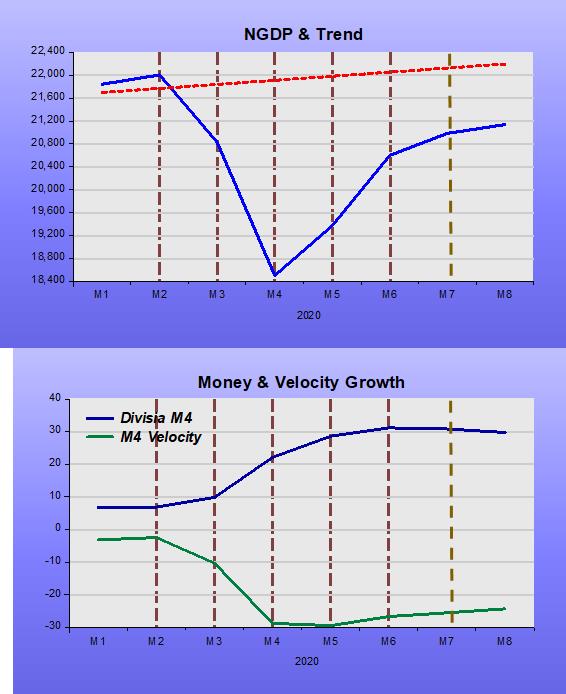

The next chart zooms in on the “new normal” chart shown in the first picture above. To explain the recent behavior of nominal spending (NGDP), I use the QTM (Quantity Theory of Money).

According to the QTM, MV=Py, to keep nominal spending (Py) growing at a constant rate, money supply (M) has to offset changes in velocity (V).

The chart shows five regions. In region 1, the Covid19 surprise increased the demand for money (velocity falls). Since the money supply barely changed, NGDP drops. In region 2, the Covid19 shock intensifies the demand for money (velocity drops more). Although money supply growth rises, it does so by less than required to keep NGDP at least stable. In region 3, velocity stabilizes while money supply growth increases. NGDP rises. In region 4 money still grows somewhat, but so does velocity, with the result being a further rise in NGDP.

In region 5, which covers the latest data point (July), we see that money growth stabilizes. Velocity, however, rises somewhat so NGDP increases but at a slower rate.

Maybe the Fed was influenced by the large number of articles and op-eds decrying that the unprecedented rates of money growth would lead to an inflationary boom down the road. In any case, money growth stopped rising. In that case, the rise in NGDP was fueled only by the small rise in velocity.

It appears, therefore, that we face a situation not of excessively strong money supply growth, but once again, although for very different reasons, a case of “not enough money”. For NGDP to rise back to the “new normal” trend, money growth will have to increase more, unless velocity rises faster,

The danger is that the Fed will not make up fully for the drop in NGDP, starting on a “new-new normal”, characterized by an even lower level of aggregate nominal spending. The new target of getting inflation to average 2% will also remain a distant dream…