Conor Sen discusses inflation:

Those who argue that the U.S. Federal Reserve should keep interest rates low typically point to the same piece of evidence: The central bank’s preferred measure of inflation remains below its 2 percent target, suggesting that the economy still needs stimulus.

What they ignore is that during the dot-com and housing booms of the 1990s and 2000s, this logic would have led to bigger bubbles — and bigger busts.

Stop right there.

That´s the best argument against inflation targeting!

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the economy was buffeted by (positive) productivity shocks. That increases RGDP growth and reduces inflation. If the fall in inflation induces the Fed to adopt a more expansionary monetary policy, the result will be nominal instability.

But those were not straightforward times. Other relevant shocks were taking place. There was the Russia/LTCM shock of 1998, the oil shock of 1999 and Y2K (1999), terrorist attack (9/11/2001), the Eron et al also in 2001. In 2003-08 there were also back to back significant negative oil shocks.

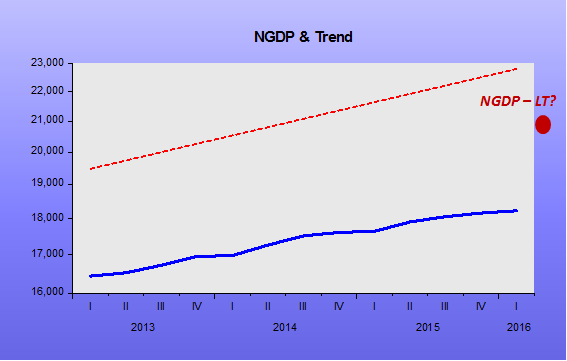

Instead of gauging the stance of monetary policy by the up´s and down´s of the Fed Funds rate, you should look at the behavior of NGDP relative to trend.

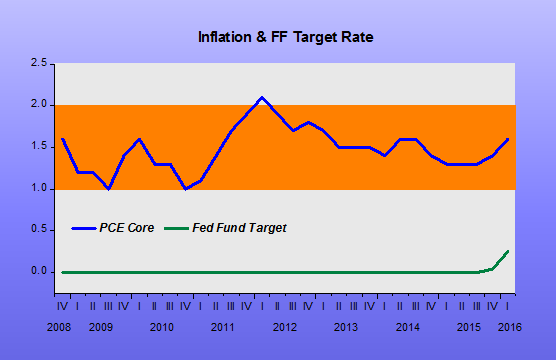

The chart puts the NGDP Gap (the behavior of NGDP relative to its trend path) and PCE Core inflation.

It seems that in its reactions to those shocks, the Fed initially “oversupplied” money between 1998 and 2000 and then, “undersupplied” money between 2001 and 2003. During most of that period, inflation remained below “target” because the positive supply shock was preponderant.

Then Conor Sen writes:

The bursting of the subprime bubble was particularly disastrous, forcing the Fed and Congress to take extraordinary measures to keep the financial system afloat and contain the economic damage. One can only wonder how much worse the episode would have been — and whether Congress would have found the political will to pay for even bigger bailouts — if the Fed had further fueled the boom by conducting even looser monetary policy. We should be glad the bubble got no bigger than it did.

He couldn´t be more wrong. What happened is that with the end of the productivity boom and the reemergence of a strong negative supply (oil) shock, core inflation ticked above the then implicit inflation target between 2005 and 2007.

But that was enough to bring on the inflation paranoia, which is quite evident in the 2008 FOMC Transcripts.

The result was that in 2008 monetary policy was severely tightened, with NGDP taking a deep and prolonged dive.

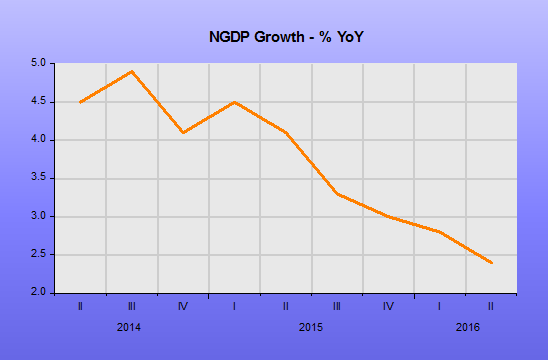

Now, you could ask: Why didn’t inflation become deflation? It certainly was on the way to that, but in 2009 the Fed reversed course and put NGDP growth back into positive territory. The chart illustrates.

Something interesting to note: Since the crisis, core inflation has not behaved differently from what it did during 1997-2004, remaining mostly below target.

The difference is that now, instead of a productivity boom, we´re having a productivity slump. Inflation should be higher. It isn´t because NGDP growth has remained on a much lower path than before.

However, likely because the NGDP level path has been so much lower, opportunities for productivity enhancement investments have been rare. This has important feed-back effects and may be the main reason for the appearance of “feelings” of “Great Stagnation”.

At the end, Conor Sen confirms “inflation” as the proper target. But one that should be complemented by other indicators

Of course the Fed has to focus on inflation in making its monetary policy decisions. But officials should keep in mind that core PCE is not the only measure, and factor in other indicators such as employment and the behavior of asset markets. If they do so, the case for removing stimulus in the near future will look a lot stronger.

Life for the Fed and for the market would be much simpler if, instead of an elusive “inflation target”, the Fed targeted a trend level path for NGDP, much like it implicitly did from 1987 to 2007.

HT David Beckworth