A James Alexander post

Seems like Ben Bernanke has tried to get the final word before the next FOMC meeting, as sort of ex officio member. In a blog post he strongly defends negative interest rates and rails against raising the inflation target as if people were proposing 10% inflation targets. It seems no more than 2% inflation or we are all doomed. He does mention NGDP targeting but misunderstands it badly.

His post is so full of errors that it has hard to know where to start.

“Nominal interest rates are very low, and in a world of excess global saving, low inflation, and high demand for safe assets like government debt, there’s a good chance that they will be low for a long time.”

What does “excess global saving” mean? In macroeconomics “saving” is part of an identity equal to “investment”. Like MV=PY. Saving can’t be in excess it has to equal investment.

Being generous, perhaps he means there is too much demand to hold money? In which case, central banks should supply more to bring demand and supply into balance; or threaten to do so until demand increases and more is spent.

Interest rates are my first love

“When the next recession arrives, there may be limited room for the interest-rate cuts that have traditionally been central banks’ primary tool for sustaining employment and keeping inflation near target.”

This is a very basic error. It is a view that sees interest rates as the primary tool, rather than a symptom of monetary policy. Interest rates react to nominal growth expectations and these are driven by central banks supplying more or less high-powered money. Interest rates are low in the US because nominal growth expectations are low. Yet US Base Money has been shrinking at between 3-6% for over a year now. Doesn’t he know this?

Gets the case for NGDP Targeting very wrong

“Outside the United States, Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has expressed openness to targeting nominal GDP (which essentially involves targeting a higher inflation rate when GDP growth is low) … ”

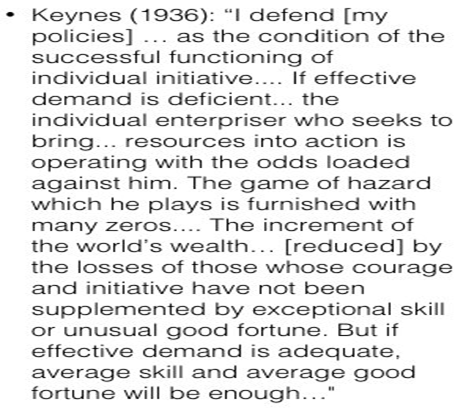

Err, just no, that is not what it is. NGDP targeting asks for a stable growth of NGDP. It particularly targets expectations of growth as expectations drive action – just like in the theory of targeting inflation expectations. Targeting expectations also avoids near term noise in actual data, just like with inflation targeting. More generally, it provides nominal stability, thus preventing the occurrence of major demand shocks, especially those that flow from monetary policy reacting to supply shocks (like the one Bernanke himself presided over in 2008).

NGDP targeting does not target “higher inflation”. It is agnostic about inflation. Market Monetarists are often very sceptical that inflation can be accurately measured. And, they are certainly sceptical a central bank can target inflation. It is a sprite and it makes (Real) GDP equally hard to calculate, in real time or even forecast. People live and work in the nominal world, not the Real world.

Interest rates are best even when negative

The rest of the article is all about the pros and cons of negative interest rates (many pros) versus a higher inflation target (many cons).

The extended discussion on real rates leaves me cold. I don’t really understand what inflation is so I struggle to understand the meaning of a real interest rate and find it very hard to comprehend the neutral real rate.

I also know the public finds negative rates almost incomprehensible and regard such a policy as a total failure by “the authorities”, whoever they are. Bernanke’s strong support for negative rates shows just how out of touch he must be with real people. He claims Europeans and Japanese under these negative interest regimes are coping well. That is just not true.

He even suggests that negative rates are only temporary, and that everyone knows it, not realising that this renders them toothless, as it promises tightening around the corner.

Whoooo, don’t let the inflation genie out of the bottle

“Higher inflation has costs of its own, of course, including making economic planning more difficult and impeding the functioning of markets. Some recent research suggests that these costs are smaller than we thought, particularly at comparatively modest inflation rates. More work is needed on this issue. Higher inflation may also bring with it financial stability risks, including distortions it creates in tax and accounting systems and the fact that an unexpected increase in inflation would impose capital losses on holders of long-term bonds, including banks, insurance companies, and pension funds.”

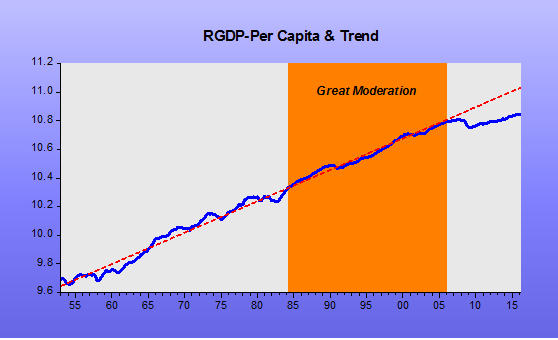

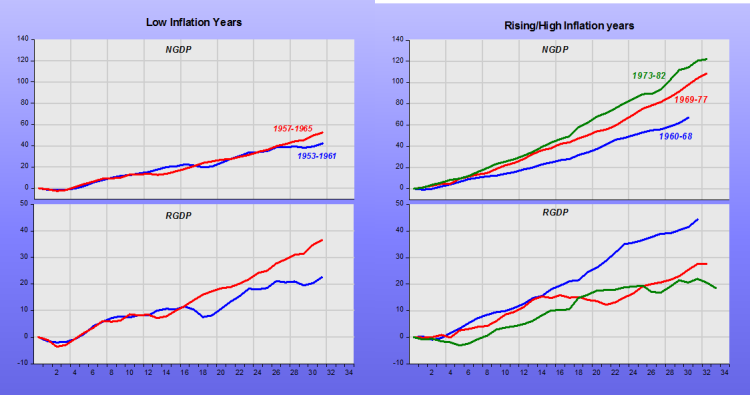

It is hard to know what “higher inflation” he is talking about. 3%, 4%? The golden eras of the US economy usually had higher inflation than today. The lowflation, or rather low nominal growth, of the Great Stagnation he helped create is the thing making economic planning more difficult and impeding the functioning of markets. Economies need healthy nominal growth to be flexible enough in rewards to allow all to see growth in returns, some faster than others. At a crushing 3% or less nominal growth, at a depressed NGDP level (see chart below), this cannot happen.

Downwardly sticky wages are a massive problem causing recessions, but also constraining productivity growth in a low nominal growth environment. Yet Bernanke calls for more work! What have the thousands of central bank-employed PhDs been doing all these years? Twiddling their thumbs.

Is Bernanke talking his own book and/or that of his employers?

Financial stability risks are worst in deflationary environments, no question, just look at the Great Recession or the Great Depression. Tax and accounting issues arise only when inflation is well above 10% or more, and then they are still quite theoretical rather than real. Bernanke seems to be fearing a return to the worst years of the 1970s. He can’t be serious.

And then he worries about his various new employers seeing capital losses from betting wrong on financial markets. Well, does he think they should be guaranteed winnings?

The article goes on and on with the familiar litany of worries about higher inflation hurting savers, needing political approval etc. etc. No one is proposing 10% inflation. Just 3 or 4%, or better still a commitment to a level target, an average target, and not constant undershooting. Or, better, a nominal income/NGDP level target.

He seems to be randomly firing at straw men. He even clutches at the idea of more fiscal activism, as if that could work without threatening the inflation target. He well knows the Fed would offset it at the first opportunity.

He never used to be quite this bad, as Scott Sumner tirelessly points out when Market Monetarists get fed up with these manias of the modern Bernanke.

Perhaps he’s worried about his lowflation legacy crumbling. It couldn’t happen soon enough for us. He seems to have become a caricature of things he may have ridiculed in the past: an interest rate junkie and an inflation-targeting nutter.