The trinity is comprised of the “star variables” y*, u*, and r*, which denote, respectively, potential output, natural rate of unemployment and neutral interest rate.

According to Bernanke:

Changes in policymakers’ estimates of these variables thus reflect reassessments of the economic environment in which policy must operate.

DeLong is more forceful:

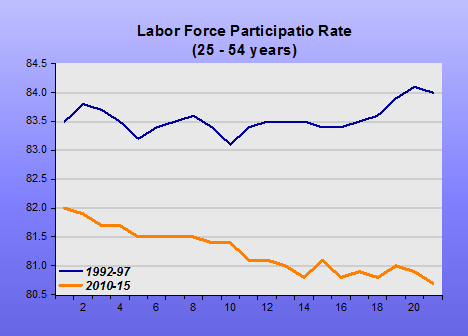

The only way to resolve the question in a satisfying way is to test it: to push the economy beyond the estimated potential growth rate and see if inflation rises…. Bernanke argues that Fed officials are willing to be a little patient with the economy, to see whether running it a little hot brings more workers into the labour force and encourages productivity-enhancing investments. It certainly seems clear to me that overshooting is the right way for the Fed to err….

But I am less confident than Mr Bernanke in the Fed’s openness to overshooting. It did not exactly intend to run the unemployment rate experiment that demonstrated how wrong its previous projections had been…. Now, the Fed looks all too willing to revise down its GDP growth projections without ever really testing them…. There is far too little radicalism at the Fed. It risks making permanent a low-growth state of affairs which is largely a consequence of its own excessive caution.

It gets worse. In “Fed Officials Challenge Decades of Accepted Wisdom on Inflation”, we read:

Nalewaik suggests that a return to a world in which inflation expectations and actual inflation become more tightly linked, as they were before the mid-1990s, may not be in the cards.

As Nick Rowe tweeted, if the Fed´s inflation target is credible, as it has been for more than 20 years, there should be no correlation between expected and actual inflation. This is an application of Friedman´s “Thermostat”. In 2003, Friedman gave the simplest explanation for the “Great Moderation” with his “thermostat analogy”. In essence, the new found stability was the result of the Fed (and many other Central Banks) stabilizing nominal expenditures. In that case, from the QTM, according to which MV=PY, the Fed managed to offset changes in V with changes in M, keeping nominal expenditures, PY, reasonably stable. Note that PY or its growth rate (p+y), contemplates both inflation and real output growth, so that stabilizing nominal expenditures along a level growth path means stabilizing both inflation and output.

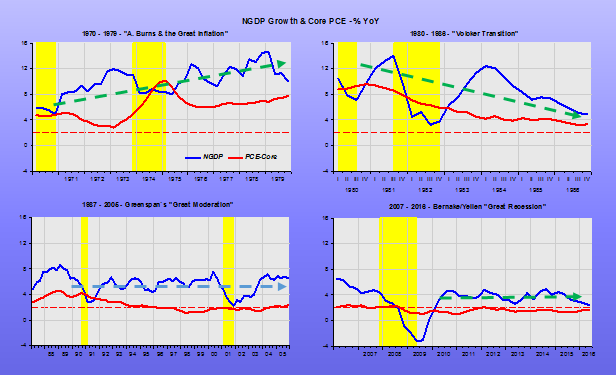

The thermostat analogy come out very clearly in the panel below.

While monetary policy was loose and NGDP growth was trending up, the outcome was runaway inflation.

To get inflation down, Paul Volcker experimented with NGDP growth, bringing it down.

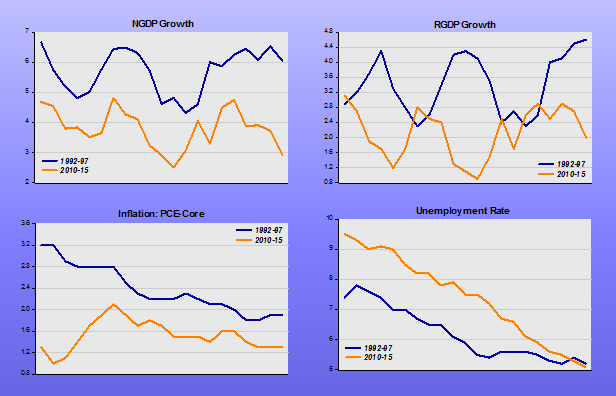

While the Greenspan Fed kept NGDP growth at an adequate stable level, the Bernanke/Yellen Fed first depressed NGDP and then kept it growing at an inadequate level. That fact is sufficient to explain both the “sluggish” recovery and “too low” inflation.

If only the Fed could forget about the “star trinity” and experiment with NGDP growth, the main determinant of the economic environment…

Instead, they get “desperate”

Central bankers and governments must come up with new policies to buffer their economies against persistently low interest rates that threaten to make future recessions deeper and more difficult to avoid, a top Federal Reserve official said on Monday.

Setting higher inflation targets, tying monetary policy directly to economic output, instituting government spending programs that automatically kick in during economic downturns, and boosting investment in education and research are all policies that should be considered, San Francisco Fed President John Williams said.