Just as confusing as the effects of the sequester itself is to figure out when it starts:

Leaders in Washington know they are approaching the moment when the so-called sequester spending cuts are set to take effect — but they apparently are confused about when exactly that moment is.

The White House confirmed today that President Obama will meet with congressional leaders to discuss the sequester on Friday, the day the sequester takes effect. That spurred congressional Republicans to criticize the president for scheduling a meeting after the sequester starts. Aides to both Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., and House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, told CBS News that the sequester officially becomes law at 12 a.m. ET on Friday – that’s midnight from Thursday into Friday.

Shortly after that, White House press secretary Jay Carney told reporters, “My understanding is it happens at midnight on Friday, 11:59.” In other words, the White House meeting would take place just before the sequester takes effect, not after.

In fact, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (H.R.8 and Public Law 112-240) lays out the timing this way, in Section 901(e): “Sequester- On March 1, 2013, the President shall order a sequestration for fiscal year 2013 pursuant to section 251A of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.”

Congressional sources tell CBS that this effectively means the sequestration starts when Mr. Obama wants it to. By law, he must sign an order to start the sequestration some time – anytime – on Friday. At that point, the Office of Management and Budget will release a report on the specifics of agency cuts.

At that moment ‘doomsday’ will have arrived.

As ‘sparring’ for my arguments, I´ll single out Laura D´Andrea Tyson. In addition to being an academic (Haas School of Business UC-Berkeley), she´s also been Chairperson of the CEA and Head of the National Economic Council in President Clinton´s administration. In addition, she´s a ‘representative agent’ of those in the ‘doomsday camp’.

She recently wrote a piece at Project Syndicate with a catchy title: America´s Sequestered Recovery. According to her:

The United States is confronting another round of cuts in federal government spending, this time threatening to trim at least 0.5 percentage points from GDP growth and to precipitate a loss of at least one million jobs. Automatic across-the-board spending cuts, the so-called “sequester,” would reduce spending by $85 billion, with defense programs cut by about 8% and domestic programs by about 5% this year – and with additional cuts of comparable dollar amounts every year until 2021.

Anemic government spending, not profligacy, has been a major factor behind the economy’s lackluster recovery. According to a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office, large spending cuts by state and local governments – and, more recently, a significant reduction in federal spending – have contributed to the unusual and prolonged weakness of aggregate demand.

In recent speeches, US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and Vice Chair Janet Yellen have described fiscal policy at the local, state, and federal levels as a powerful headwind slowing the economy’s return to full employment. In the year after the recession ended, discretionary spending at the federal, state, and local levels boosted growth at about the same pace as in previous recoveries.

But, since then – and in sharp contrast to previous recoveries – fiscal policy has become contractionary, reducing aggregate demand and restraining growth. State and local governments have cut spending and payrolls significantly. And federal purchases of goods and services have been declining since 2010, when the temporary additional spending in the 2009 stimulus package came to an end.

As a result of a deep and persistent deficiency in aggregate demand, the US economy has been operating far below its potential output level. Real GDP fell by 8% relative to its noninflationary potential in 2008-2009, and has remained about 8% below its previous growth path ever since.

The significant loss of current and future potential output is all the more remarkable, because it has occurred despite a sustained and unprecedented effort by the Fed to boost demand and hasten the recovery. Fed officials have repeatedly expressed concern that the prolonged weak recovery will inflict future pain in the form of slower long-run growth.

I just love this last bit, but will leave comment on it for last.

Laura Tyson makes three statements to justify her conclusion, expressed in the title to the article, that “the sequester will ‘sequester’ the economic recovery”.

S1. In the year after the recession ended, discretionary spending at the federal, state, and local levels boosted growth at about the same pace as in previous recoveries.

Below the chart behind the statement.

The statement seems ‘false’. Real Government (Federal, State & Local) Purchases during the first year of recovery were smaller than during the first year of recovery after the 1990/91 recession and way below purchases during the first year of recovery after the 2001/01 recession. Nevertheless, RGDP went up by as much as in the first year following the 2001/01 recession and significantly more than after the 1990/91 recession.

S2. But, since then – and in sharp contrast to previous recoveries – fiscal policy has become contractionary, reducing aggregate demand and restraining growth.

The Chart for the statement follows:

Statement 2 seems ‘correct’. Growth is restrained when compared to the previous recoveries while government purchases have decreased. But it is worth noting that growth in 1992-94 was better than in 2002-05, despite real government purchases remaining ‘flat’ in 1992-94 while they increased in 2002-05.

S3. The significant loss of current and future potential output is all the more remarkable, because it has occurred despite a sustained and unprecedented effort by the Fed to boost demand and hasten the recovery.

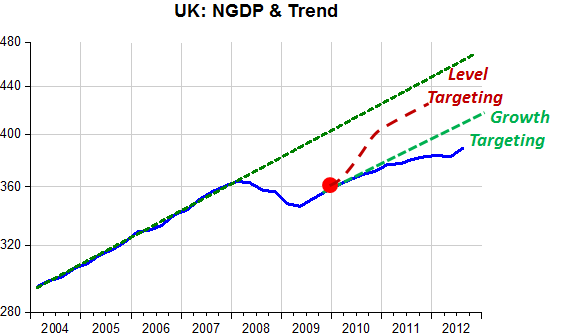

The chart below is an imperfect but useful representation of the statement – sustained and unprecedented effort by the Fed. The chart compares nominal aggregate spending (NGDP) in the first year of recovery and during the subsequent 10 quarters.

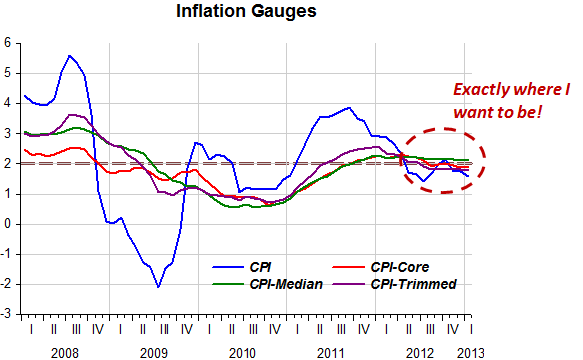

We could agree on ‘sustained’ – after all, NGDP is growing. But as to ‘unprecedented’ we can agree it´s not! Spending growth, something closely controlled by the Fed, has been much smaller than in previous recoveries, especially in the ‘subsequent 10 quarters’. In other words, monetary policy is ‘tight’.

It´s easy to say “it´s due to restrictive fiscal policy”, but I have my doubts. This cycle has been markedly different from other post war cycles, in particular regarding the ‘down phase’, so it may not be ‘illuminating’ to compare just the recovery phase of the cycles and emphasize the behavior of government spending (because, after all, monetary policy accommodation is ‘unprecetented’).

The next chart illustrates the recession phase of the cycle. It would be hard to argue that the depth of the recession was due to the absence of fiscal stimulus. Note that the initial stage of the recession was quite mild, especially when compared to the 1990/91 recession, despite comparable government spending. But while government spending kept on rising real output growth ‘jackknifed’ after mid-2008.

The recession phase was longer and went much deeper than in the other occasions. But you wouldn´t have thought that possible by just looking at the behavior of government purchases. So let´s take a peek at the stance of monetary policy – represented by the behavior of NGDP – in the different recession phases.

It certainly helps clear things up. There is total consistency, and note that it was only after monetary policy tightened the screws even more (despite lowering interest rates all the way to ‘zero’) that a run-of-the-mill recession – that could be compared favorably with the mild 1990/91 recession – turned “Great”.

The main lesson is that comparing the recovery phase of the different cycles is inappropriate and misleading because the recession phases were so markedly different. That also had the effect of increasing the public deficit and debt to much higher levels in this cycle than in other occasions. But it was raised above what it would have if monetary policy had not been – and still is – so restrictive.

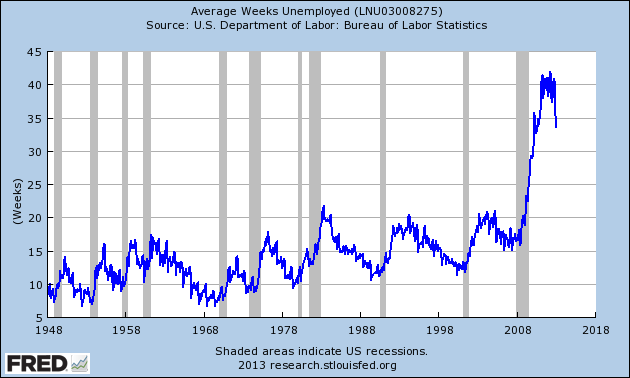

Just to see how misleading it is just comparing the recovery phases of the cycle, from the chart below, describing the behavior of employment in recoveries, one would think that we´re doing much better than after the 2001 recession. But when you look at the recession phase, ‘reality slaps you in the face’. In other words, it´s not just growth rates that matter, and that´s what most people focus on. In the present case, ‘levels’ are defining.