In his latest post Bernanke takes on the WSJ editorial “The Slow-Growth Fed?”:

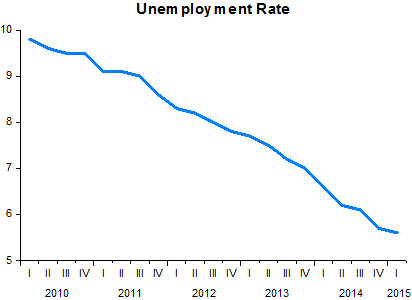

The unemployment rate is a better indicator of cyclical conditions than the economic growth rate, and the relatively rapid decline in unemployment in recent years shows that the critical objective of putting people back to work is being met. Growth in output has been slow, despite solid job creation, because productivity gains have been slow—perhaps as the result of the financial crisis, which hammered new business formation and investment in research and development, perhaps for other reasons. But nobody claims that monetary policy can do much about productivity growth. Where it can be helpful is in supporting the return to full employment, and there the record has been reasonably good. Indeed, it seems clear that the Fed’s aggressive actions are an important reason that job creation in the United States has outstripped that of other industrial countries by a wide margin.

The WSJ also argues that, because monetary policy has not been a panacea for our economic troubles, we should stop using it. I agree that monetary policy is no panacea, and as Fed chairman I frequently said so. With short-term interest rates pinned near zero, monetary policy is not as powerful or as predictable as at other times. But the right inference is not that we should stop using monetary policy, but rather that we should bring to bear other policy tools as well. I am waiting for the WSJ to argue for a well-structured program of public infrastructure development, which would support growth in the near term by creating jobs and in the longer term by making our economy more productive. We shouldn’t be giving up on monetary policy, which for the past few years has been pretty much the only game in town as far as economic policy goes. Instead, we should be looking for a better balance between monetary and other growth-promoting policies, including fiscal policy.

In “The Fed´s Lullaby”, I said that the Fed was happy with satisfying “the other mandate”! Note that BB doesn´t mention inflation!

“Growth in output has been slow, despite solid job creation, because productivity gains have been slow—perhaps as the result of the financial crisis”. Not so subtly he says “it was not my (the Fed´s) fault. However, that argument doesn´t stand up to scrutiny.

The panel below puts productivity and unemployment side by side for the following periods: 1983.I – 1995.1; 1995.II – 2003.IV; 2004.I – 2014.IV.

Note that productivity growth rises when unemployment increases (as expected). That´s not so evident for 1995.2 to 2003.IV because throughout this time productivity was booming. Nevertheless, there´s a big difference in productivity growth between 1995.II – 2000.IV at 2.5% and 2001.I – 2003.IV, when unemployment was on the rise, at 3.6%.

Note also that between late 1992 and early 1995 (top row) productivity growth was nonexistent, and lower than what has been observed since early 2011, nevertheless real GDP remained close to trend (see RGDP & Trend chart).

What Bernanke still fails to address after having blogged for one month is WHY the Fed, under his command, allowed a depression to materialize. If he had only acknowledged early on after 2008 the mistake of letting nominal spending (NGDP) tank he would have “guessed” the solution. Long-term real growth is not the province of the Fed. The best the Fed can do to allow the economy to “flourish” at the highest level is to maintain nominal stability, a task in which it failed miserably. It´s no good and no use now calling for “a better balance between monetary and other growth promoting policies”, whatever that means.

As George Selgin wrote today, it may be late in the game to regain much of what was lost because:

You see, unlike some economists, although I’m happy to allow that an increase in the Fed’s nominal size, which is roughly equivalent to a like increase in the monetary base, is neutral in the long run, I don’t accept the doctrine of the neutrality of increases in the Fed’s relative size. I believe that Fed-based financial intermediation is a lousy substitute for private sector intermediation, and that as it takes over, economic growth suffers. The takeover is, in other words, financially repressive.

Which means that the level of spending is, after all, not the only relevant indicator of whether the Fed is or isn’t going in the right direction. Another is the real size of the Fed’s balance sheet relative to that of the economy as a whole, which measures the extent to which our central bank is commandeering savings that might otherwise be more productively employed. Other things equal, the smaller that ratio, the better.

And there, folks, is the rub. If you want to know the real dilemma facing the FOMC, forget about the CPI, oil prices, and last quarter’s weather. Here’s the real McCoy: NGDP growth is too low. But the Fed is too darn big.

Yes, Bernanke, by your misguided policies you´ve made the Fed too big AND mostly useless!