A Mark Sadowski post

In a recent post James Alexander caught Danny Blanchflower tweeting that he thought “NGDP totally impractical due to data revisions”.

This is a familiar complaint, voiced for example by Goodhart, Baker and Ashworth in January 2013.

There are numerous problems with this line of thinking.

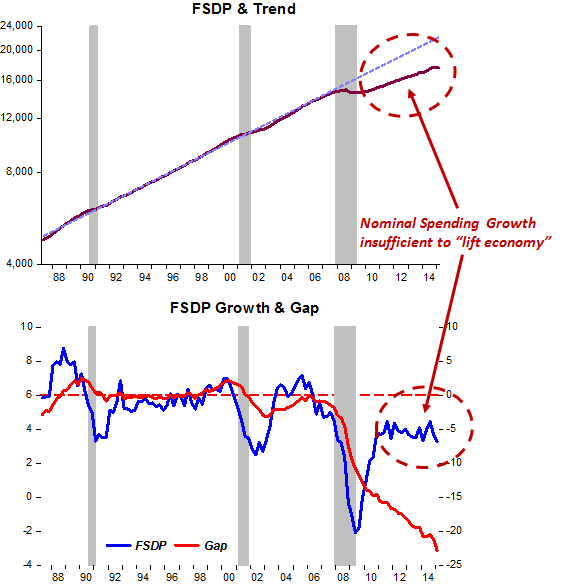

First of all, central banks shouldn’t be targeting past values of economic variables anymore than one should attempt to drive a vehicle on a superhighway by looking in the rearview mirror. Arguably the world’s major central banks tried doing that in 2008, and we are still living with the results. Since central banks should only be targeting the expected values of economic variables, bringing up the issue of data revisions reveals a level of obtuseness that borders on the ridiculous.

And as irrelevant as the issue of data revisions is to the proper conduct of monetary policy, although NGDP levels tend to be revised, that certainly should not imply that inflation rates are not revised. In fact the personal consumption expenditure price index (PCEPI), the inflation rate of which is the official target of the Federal Reserve, often undergoes significant revisions.

There’s two main ways of measuring the size of the revisions of the components of national income and product accounts: 1) Mean Revision (MR) and 2) Mean Absolute Revision (MAR). For rate targeting MAR is the more appropriate measure, and in fact the MAR of inflation is usually smaller than the MAR of NGDP. However, for level targeting MR is more appropriate.

Interestingly, at least in the US (Page 27):

“The MRs for the price indexes for GDP and its major components are generally not smaller than those for real GDP and current-dollar GDP and its major components.”

In fact, over 1983-2009 the MR for the final revision to quarterly NGDP is 0.14, whereas over 1997-2009 the MR for the final revision to the GDP deflator and the PCEPI is 0.20 and 0.12 respectively. And over time the revisions have trended downward.

So I suspect that the MR for NGDP is smaller than the MR for PCEPI over 1997-2009.

Which means the claim you frequently hear that NGDP revisions are larger than inflation revisions is pure grade A horse manure. You will never see any evidence supporting this mindlessly repeated spurious claim, because no such evidence exists.

And, finally, inflation is a totally artificial construct requiring that we come up with an estimate of the extraordinary abstraction known as the “aggregate price level.” To see how preposterous this is imagine equating the aggregate price level between what it is now and what it was in say 14th century England. The goods and services are so different it requires the complete suspension of one’s disbelief.

In particular, PCEPI inflation is the difference between nominal PCE and real PCE, meaning PCEPI inflation is nothing more than the estimated residual between a truly nominal variable, which is relatively straightforward to measure, and a real variable, which is fundamentally an exercise in crude approximation.

It’s high time that central banks moved beyond the near medieval practice of targeting real variables and/or their residuals, and started targeting truly nominal variables, which according to the accepted tenets of monetary theory is their proper domain.