In London, recently, St Louis Fed president James Bullard restated the Bank´s ‘new view’:

The St. Louis Fed had been using an older narrative since the financial crisis ended. That narrative has now likely outlived its usefulness, and so it is being replaced by a new narrative. The hallmark of the new narrative is to think of medium- and longer-term macroeconomic outcomes in terms of regimes. In this new narrative, the concept of a single, long-run steady state to which the economy is converging is abandoned, and is replaced by a set of possible regimes that the economy may visit. Regimes are generally viewed as persistent, and optimal monetary policy is viewed as regime dependent. Switches between regimes are viewed as not forecastable.

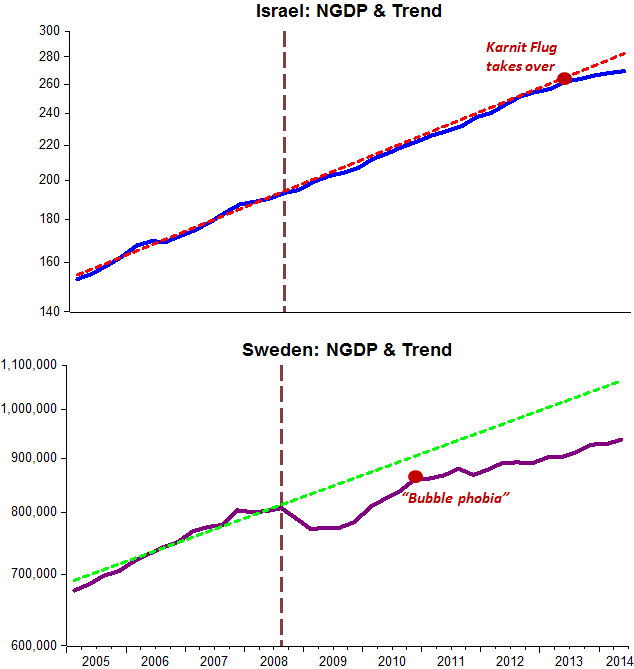

Unfortunately, Bullard gets it wrong. It is not monetary policy that is regime dependent but regimes that are monetary policy dependent. In other words, the Fed is not passive, but instrumental in building regimes.

History is very clear on that point.

In the 1960s, monetary policy worked double-shift to build the high inflation (“Great Inflation”) regime that blossomed in the 1970s.

According to Arthur Okun, Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) staff member (1961-62), member (1964-67) and Chairman (1968-69):

The stimulus to the economy also reflected a unique partnership between fiscal and monetary policy. Basically, monetary policy was accommodative while fiscal policy was the active partner. The Federal Reserve allowed the demands for liquidity and credit generated by a rapidly expanding economy to be met at stable interest rates”

Throughout the 1970s, Fed Chairman Arthur Burns conducted monetary policy in such a way as to entrench the “Great Inflation” regime. According to Burns:

We are in the transitional period of cost-push inflation, and we therefore need to adjust our policies to the special character of the inflationary pressures that we are now experiencing. An effort to offset, through monetary and fiscal restraints, all of the upward push that rising costs are now exerting on prices would be most unwise. Such an effort would restrict aggregate demand so severely as to increase greatly the risks of a very serious business recession.

In his view, monetary policy could at most mitigate the unemployment effects of supply shocks. No wonder nominal spending growth showed a rapidly rising upward trend all through the 1970s. High and rising inflation was the consequence.

Later, Paul Volcker worked hard to change the regime. In his first FOMC meeting as Chairman in 1979, Volcker “defined his moment” by asserting:

Economic policy has a kind of crisis of credibility. As a result, dramatic action to combat inflation would not receive public support without more of a crisis atmosphere.

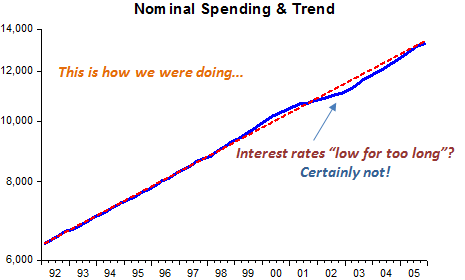

I define the seven-year period going from the fourth quarter of 1979 to the fourth quarter of 1986 as the “Volcker Transition.” That is when the US economy transitioned from a high inflation and high volatility regime, to one characterized by more-stable real output and lower and steadier rates of inflation. The result of the Volcker Transition is the “Great Moderation” that extends, under Greenspan, from 1987 to 2007.

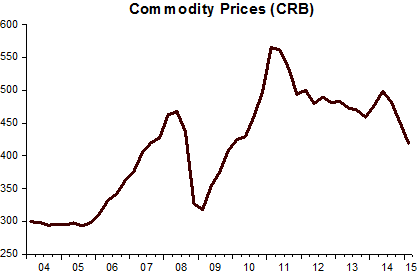

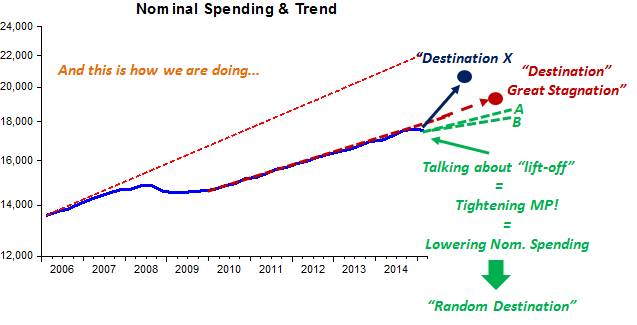

Bernanke´s misguided monetary policy, heavily influenced by fears of inflation from oil price shocks, broke the spell. The outcome was the “Great Recession” regime, quickly followed by the “Great Stagnation” regime.

This is a good place to introduce another Fed Bank that does not capture the fact that monetary policy is vital in determining the regime. Four years ago, Liberty Street, the blog of the New York Fed wrote The Great Moderation, Forecast Uncertainty, and the Great Recession:

The Great Recession of 2007-09 was a dramatic macroeconomic event, marked by a severe contraction in economic activity and a significant fall in inflation. These developments surprised many economists, as documented in a recent post on this site. One factor cited for the failure to anticipate the magnitude of the Great Recession was a form of complacency affecting forecasters in the wake of the so-called Great Moderation. In this post, we attempt to quantify the role the Great Moderation played in making the Great Recession appear nearly impossible in the eyes of macroeconomists.

And concludes:

In sum, our calculations suggest that the Great Recession was indeed entirely off the radar of a standard macroeconomic model estimated with data drawn exclusively from the Great Moderation. By contrast, the extreme events of 2008-09 are seen as far from impossible—if unlikely—by the same model when the shocks hitting the economy are gauged using data from a longer period (third-quarter 1954 to fourth-quarter 2007). These results provide a simple quantitative illustration of the extent to which the Great Moderation, and more specifically the assumption that the tranquil environment characterizing it was permanent, might have led economists to greatly underestimate the possibility of a Great Recession.

From reading Bullard, that´s exactly what you would get because:

The upshot is that the new approach delivers a very simple forecast of U.S. macroeconomic outcomes over the next two and a half years. Over this horizon, the forecast is for real output growth of 2 percent, an unemployment rate of 4.7 percent, and trimmed-mean personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation of 2 percent. In light of this new approach and the associated forecast, the appropriate regime-dependent policy rate path is 63 basis points over the forecast horizon.

The chart below comprises the period considered by Liberty Street. Note that in the late 50s, the relatively small and brief negative NGDP growth was sufficient to thump RGDP growth, even harder than the supply shocks of the 70s or the tightening of spending during the Volcker Transition.

According to Robert Lucas (Econometric Policy Evaluation, a critique, 1976), forecasts are regime dependent. So, if you change policy, you change the regime (and also the forecasts).

Liberty Street estimates the model across regimes, so that the Great Recession becomes “far from impossible”.

I identify the Great Stagnation regime as a low volatility regime. That characteristic (low vol) is shared with the Great Moderation regime. But that is very misleading. Once you take into account the different nominal and real growth rates in the two periods, you understand how “sub-optimal” the present regime is!

The Tables below illustrates for the 2010-2016 and 1992-1997 (halcyon days of the Great Moderation).

| NGDP | 2010 – 2016 | 1992 – 1997 |

| Growth (% YoY) | 3.7% | 5.6% |

| Standard Deviation | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| RGDP | ||

| Growth (% YoY) | 2.1% | 3.5% |

| Standard Deviation | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| CPI Core | ||

| % YoY | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Standard Deviation | 0.4 | 0.5 |

Certainly a steep price to pay for having inflation a bit below target!