Antonio Fatás writes “The missing lowflation revolution”:

It will soon be eight years since the US Federal Reserve decided to bring its interest rate down to 0%. Other central banks have spent similar number of years (or much longer in the case of Japan) stuck at the zero lower bound. In these eight years, central banks have used all their available tools to increase inflation closer to their target and boost growth with limited success. GDP growth has been weak or anemic, and there is very little hope that economies will ever go back to their pre-crisis trends…

… Now we have learned that either all central bankers are as incompetent as the Bank of Japan in the 90s or that the phenomenon is a lot more natural, and likely to be repeated, in economies with low inflation, more so when the natural real interest rates is very low…

… My own sense is that the view among academics and policy makers is not changing fast enough and some are just assuming that this would be a one-time event that will not be repeated in the future (even if we are still not out of the current event!).

The comparison with the 70s when stagflation produced a large change in the way academic and policy makers thought about their models and about the framework for monetary policy is striking. During those years a high inflation and low growth environment created a revolution among academics (moving away from the simple Phillips Curve) and policy makers (switching to anti-inflationary and independent central banks). How many more years of zero interest rate will it take to witness a similar change in our economic analysis?

Fatás succinctly lays out the problem. Interestingly, since the late 1990s, many have been concerned about “Monetary Policy in a Low Inflation Environment”, among them, Bernanke himself! For those interested, I provide a nontechnical essay from 2001 (with references within).

Apparently, when “push comes to shove”, it was all forgotten!

For the past seven years, Market Monetarists, under the guidance of Scott Sumner have proposed a monetary regime change. The new regime would have the Fed (and other central banks) level target nominal GDP.

In a sense, this proposal simply involves making explicit something that was only implicit during the “Great Moderation”, being, in fact, responsible for that outcome. That´s good, because it won´t be a “shot in the dark”. We´ve been there.

Over the past seven years, people who never thought themselves as “market monetarists” have come out in favor. For example, Christina Romer, a former Obama head of the CEA and Harvard professor Jeffrey Frankel. Even Simon Wren-Lewis, a pillar of the New Keynesian school, is coming around to the idea.

There is however, one lose end. There´s a view that over the past five years, after partially recouping from the “Great Slump”, the economy lives through a “Great Moderation 2.0”. Unfortunately, the “GM 2.0” is also viewed as the “Great Stagnation”.

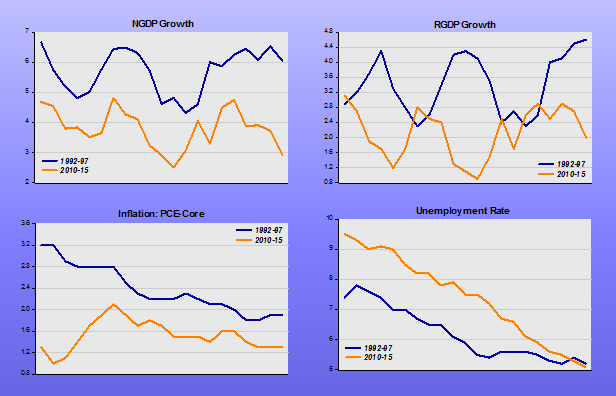

This is where the “Level Target” attached to “NGDP Targeting” comes in. To make the idea clear, I put up a set of charts that compare the “golden age” of the “GM 1.0”, the five years from 1992.IV to 1997.IV with the five years of the “GM 2.0”, from 2010.III to 2015.III.

Houston, we have a LEVEL problem!

Another point: Fatás mentions the change among academic economists, who moved away from the Phillips Curve. Now, we have academics in the Fed, like Yellen and Fischer, moving back to Phillips Curve thinking, while not abandoning inflation targeting.

Note that the unemployment rate at present is the same low rate of unemployment as in 1997, while inflation, both in 1997 and today are below the target level. In both instances, unemployment fell together with inflation!

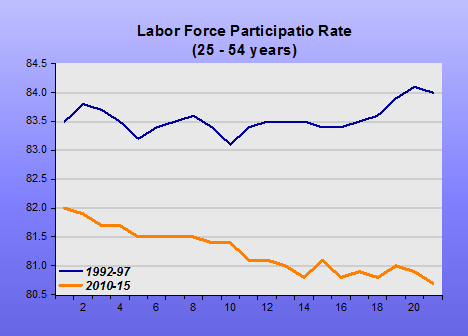

However, the unemployment then and now are not comparable magnitudes. Just look at the very different behavior of labor force participation in the two periods.

Although the level of NGDP growth is important, the fundamental level question concerns the level of NGDP, more than its growth rate. This comes out shockingly clear in the next chart. As Fatás mentions in his post:

The fact that a crisis can be so persistent and that cyclical conditions can have such large permanent effects on potential output.

Would lead us to say that, after 7 years, the original trend may not be attainable any longer. However, a trend level between today´s level and the level that prevailed all the way to 2007 may be feasible.

”

Excellent blogging. And yes, today’s unemployment is much worse than the 1990s, as your excellent graph reveals.

We are creating a less work-oriented culture in the United States through prolonged weak economic growth.

Voters are not necessarily enamored of free enterprise. Labor shortages would enamor voters of what we think is the best system, free enterprise.