In the 1980s and even before, NGDPT was widely discussed, while there was no similar discussion about IT. But as it often happens, circumstances ended up “electing” inflation as the target of monetary policy. The “circumstance” in this case was the desire of the NZ Prime Minister to make government agencies more efficient. To that purpose he required everyone to define goals and targets that would allow objective evaluations. When it came to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Governor put forward the idea of targeting inflation (at the rate set by Parliament).

The idea spread like bush-fire and sequentially several countries adopted “IT”. At that time, early 1990s, Friedman had already convinced (most) of the world that inflation was a monetary phenomenon so there was no better choice than for the Central Bank to conduct monetary policy in such a way as to avoid inflation getting “out of hand”. Even an inflation prone country like Brazil had success with IT which was introduced in early 1999 concurrently with a massive (almost 100%) devaluation of the exchange rate (which had been, for the previous five years, the nominal anchor and responsible for the success of the Real Plan in ending hyperinflation).

A period of low and stable inflation took over, even for many countries that never formally adopted the target. The US, for example, is one such case.

Almost a quarter of a century later “IT” is being questioned. A good summary of the discussion is David Beckworth´s “Inflation Targeting – A Monetary Policy Regime whose time has come and Gone”. The abstract reads:

Inflation targeting emerged in the early 1990s and soon became the dominant monetary-policy regime. It provided a much-needed nominal anchor that had been missing since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Its arrival coincided with a rise in macroeconomic stability for numerous countries, and this led many observers to conclude that it is the best way to do monetary policy. Some studies show, however, that inflation targeting got lucky. It is a monetary regime that has a hard time dealing with large supply shocks, and its arrival occurred during a period when they were small. Since this time, supply shocks have become larger, and inflation targeting has struggled to cope with them. Moreover, the recent crisis suggests it has also has a tough time dealing with large demand shocks, and it may even contribute to financial instability. Inflation targeting, therefore, is not a robust monetary-policy regime, and it needs to be replaced.

In many (most?) cases, “IT” is coupled with a rule for the instrument; a central bank determined interest rate (the Fed Funds rate in the US, for example). Because of that quirk, monetary policy has become synonymous with interest rate policy. And if interest rates are very low, as at present, central bankers (and analysts) only talk about the “need” to “normalize” monetary policy, i.e. get interest rates up to more “normal” levels.

The problem associated with low (or very low) policy rate has been discussed for at least 15 years in conferences and papers with titles such as “How to conduct monetary policy in a low inflation environment”, the idea being that if inflation is “low” (or “on target”), interest rates will also be “low”, so that if a shock comes along that requires interest rates to be lowered further, the ZLB will “prevent” monetary policy from being effective, that being the situation which is perceived by many today and why we hear arguments for an increase in the inflation target rate.

Ironically, you also hear the same people saying monetary policy is “easy” (because interest rates are very low). They don´t connect with their stated view that interest rates are low because inflation is low, meaning that monetary policy has been “tight” (to bring inflation down to target). They should reread their Friedman!

One problem with IT, in addition to those discussed by Beckworth is that it is “memoryless” with regards to the price level which is what matters most for economic decisions. For that reason we have also had frequent discussions about the benefits of the central bank adopting a price level target (PLT). See here for an example.

And then there is NGDP-LT (LT=level target) which is the favorite target of market monetarists. Basically, instead of having inflation running at the target rate or the price level evolving at a constant level target rate, NGDP-LT will have the central bank controlling the aggregate nominal spending (NGDP) in the economy evolving along a level target rate.

How to choose among them? You could (and people have) build models that will (hopefully) allow you to evaluate them. Another way is to do an empirical analysis where your “model” is history.

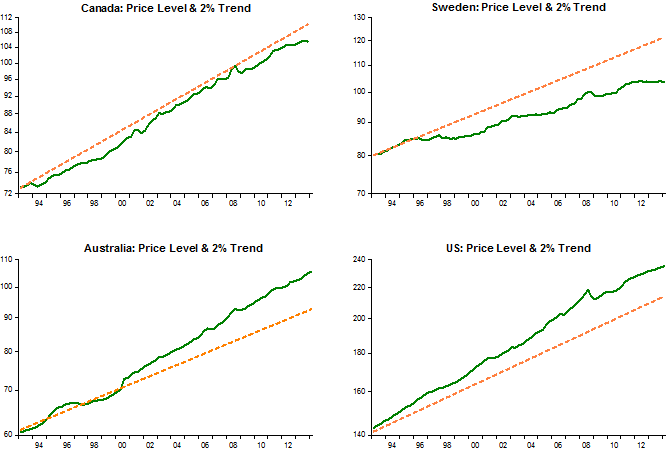

For that I picked four “inflation targeting” countries (in the US “IT” is only implicit) and see how they performed:

- As an inflation targeter

- As a price-level targeter

- As an NGDP-level targeter

The charts show (for (1)) that, with the exception of Australia (which has a target band, not rate) they were either above “target” (US) or below “target” (Sweden and Canada (with Canada showing only a small miss)).

For (2), the charts show that with the exception of Canada whose price level has remained close to the target path (as inflation has remained close to target), the others show significant divergences from the price level target path, either positive as in the case of Australia and the US or negative as in the case of Sweden.

It seems that (3) is a clears “winner”. In all cases, irrespective of inflation being a bit above or below target on average or the price level showing positive or negative divergence from the level path, NGDP remains close to the target path all the way up to the crisis. Interestingly, the country that suffered the least pain (in terms of real growth and unemployment) was Australia, not coincidently the only of the countries shown that did not allow aggregate nominal spending to diverge (especially in the downward direction) from the target path.

While the other countries are trying all sorts of “potions” to try to get back “on their feet”, including dilly-dallying with additional terms in their mandate (like “financial stability” or, in the case of the US additionally enshrine the Taylor-Rule as “policeman” for the Fed´s actions), Australia is back on the original trend level path.

Takeaway: The central bank that best takes care of maintaining NOMINAL (spending) stability does best.

PS This is the RBA´s “mission statement”:

In determining monetary policy, the Bank has a duty to maintain price stability, full employment, and the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people. To achieve these statutory objectives, the Bank has an ‘inflation target’ and seeks to keep consumer price inflation in the economy to 2–3 per cent, on average, over the medium term. Controlling inflation preserves the value of money and encourages strong and sustainable growth in the economy over the longer term.

But what they really provided was nominal stability!

Excellent blogging.

Of course, NGDP-LT is the best regime.

But looking at Australia, and considering institutional ossification at the Fed, and the zany politics of the left (Krugman) and the right (Meltzer), I wonder if the USA should just go to a higher IT, ala Australia, with a “band” of 2 percent to 3 percent.

This could, in practice, come close to NGDP-LT, but would, for public consumption, be IT to an inflation band.

The sad thing is that even 3 percent inflation would have the price-hysterics screaming bloody murder. It may require that the USA have a right-wing President and get into another war before the right stops fixating on inflation.